Vishnu Sharma

Three days after he carried the ghost of Baroodkhan on his back, my grandfather died of an undiagnosed illness. For those three days, he burned with a fever, hot as April days, and occasionally turned as cold as a December night. The white of his eyes had turned yellow, and at night he talked loudly with the ghost.

We were children, so we were not allowed to go near him, let alone touch him or talk to him. He was kept tied to a pole in the middle of his room. Yet when he saw us peeking from a small window, he smiled. His teeth had blackened by eating roots of an unknown plant that the lama was feeding him. And he moved his head, as if dancing to the music only he could hear, like a snake trying to climb a wall. He would then gesture towards the rope he was tied with and blink his eyes to call us inside to untie him. But as we went near, he would scream, “Shoo him down from my back!” and immediately laugh the laughter of helplessness, “Aha aha aha.”

Occasionally, the ghost did climb down from his back but wouldn’t leave grandfather’s room. He stood at the threshold while grandfather shouted for help before pleading with the ghost to leave him for good. Yet after a short rest the ghost crawled back upon grandfather’s back. “Ah ah ah ah!” grandfather groaned as the ghost slowly moved up, as if he was being kneaded.

My older folks, aunts and uncles and my grandmother, sat around him in turns while the lama danced in the courtyard singing lullabies to make him fall asleep. No matter how much the older folks and the lama pleaded and threatened the ghost, he refused to leave our house without my grandfather.

The ghost said, “He and I are good friends. I don’t want to live alone anymore in the woods. I’ll leave with him.”

When the ghost spoke through the lama, his meekly voice turned squeaky. Afterwards, the lama explained that the ghost was alone in the valley and said that Khopche, my grandfather, would be a good friend to be with. The ghost offered treasure in exchange, which for obvious reasons my folks refused.

Actually, my grandfather’s name was Keshav but everyone in the village called him Khopche; might be because he looked like a shovel. I think the ghost had learnt the name from the villagers.

On the morning of the third day, the lama saw the ghost and my grandfather leaving the house together. “I can’t stop them now,” he told my grandmother who for some strange reason didn’t say a word and let them leave. After they had gone, my grandfather’s body was brought out from the room and was taken for cremation.

For a long time no one in the village wanted to talk about that incident. Even when I grew older, I still didn’t dare ask anything about it to anyone. And after a long time even villagers seemed to have forgotten about grandfather and the ghost of Baroodkhan.

That was the name of the ghost. They say that the ghost still lives in Baroodkhan. Occasionally someone sees it at night, always with my grandfather. They walk holding each other’s hands. Last time my aunt, who is now very old—we had her chaurasi last year—saw my grandfather on the top of our jackfruit tree, looking at our house with teary eyes. She told us that when she touched his legs, which had now grown so long that they touched the ground, he moved his hands over her head as if to bless her but suddenly changed into a monkey and tried to snatch her left earring.

But the incident, which will be the subject of this story, happened many years after grandfather walked out of his room with the ghost. It happened during my summer vacations.

Since I was the only one studying at the time, while my other friends had left the village to work in cities or in other countries, life in the village was lonesome. Time was hard to pass and days felt stretched. If not for my mother who pressed upon me to stay a little longer, I would have, like every year, left the place within a day or two of my arrival.

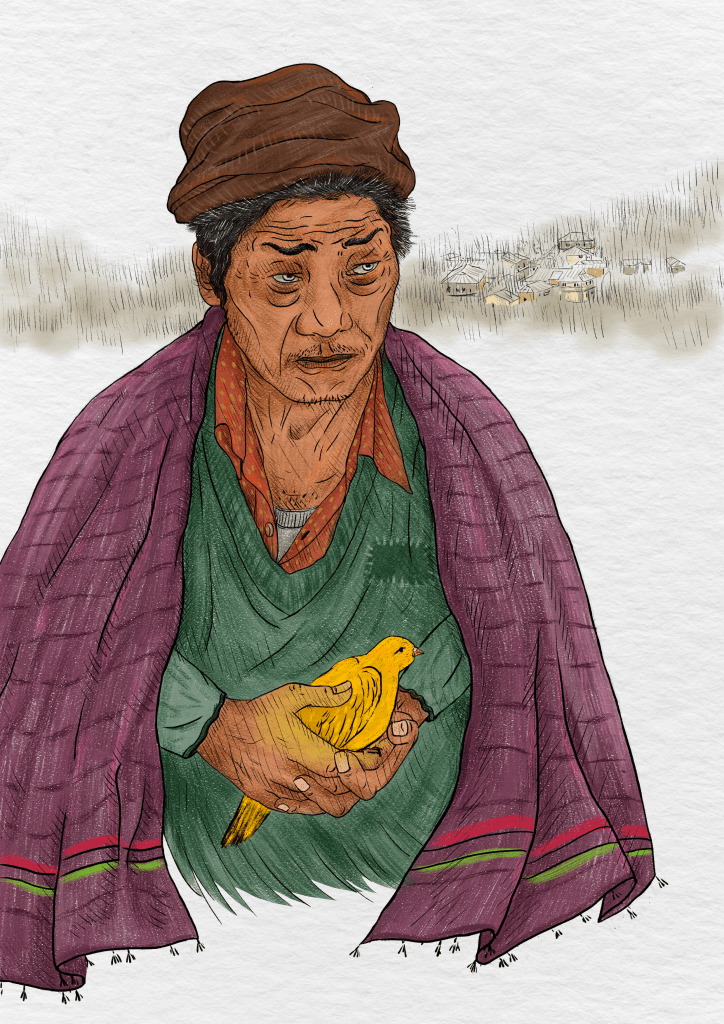

Then one day in the Hill Market, I saw a man whom I thought I knew. I couldn’t tell if I had recognized him but he looked familiar to my eyes. His image and my helplessness in not being able to recognize him tormented me no less. I felt I had seen him before but I was unable to place him. Occasionally, I would go to the market to see the man. This man sold pigeons. He had several of them. He had pigeons of all colors: white, black, grey, blue and even yellow and red. I doubted the last two were original, so, one day, just to initiate a conversation, I told him that they looked hand painted.

“I mean nobody has ever seen a red and a yellow pigeon,” I teased.

He looked at me as if he was offended but didn’t say a word. Strangely, he didn’t even try to convince me that they were real. On my fifth visit to his shop he spoke to me for the first time but just four words.

“What do you want?” he said. His cold voice made me shudder. I turned and walked away.

The next day, gathering courage, I went back to him and told him that I thought I knew him but couldn’t tell where from. I said I would be grateful if he could help me. To that, he said that he too didn’t recognize me and so he couldn’t help me.

“Don’t waste your time, boy. Go home and help your old mother,” he shooed me away.

At home I grew more restless. Even my mother noticed my bewilderment.

“I wonder if it is possible that I met him in my previous birth,” I asked my mother.

She said it was possible. Then she told me about how my father could recollect his previous life. “Then he ran a hotel at the place where the bus stop is now,” she said.

“And you believed him?”

“Why not? He knew every detail of the time.”

“Like?”

“Like, once when we met an old man, he told him his childhood name and how he had stopped at his hotel for a night when he was leaving for India to join paltan.”

Mother’s reasoning hardly made me calm. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t take the pigeon seller out of my mind. The more I tried to not remember him the more visible his image grew in my mind. I thought I was trapped and was soon losing sense of my surroundings . Wherever I went or whomever I met, I just kept thinking of him. I wished I could go back to my college and forget him. But the night before the day I was to leave the village, a hail storm followed by torrential rain washed away the road and there was no way to leave the village sooner than a week or more. So I had no option but to wait and remain in a state of great delirium.

Our village is situated just at the edge of a hill. My house, two storied, built of local bricks and plastered with mud and roofed by straws, overlooks the cliff. It is so situated that the wind from the north passes through my windows before entering the village. When the sky is not cloudy the moon shines bright over my window, and the stars, several of them, move against it. Occasionally, the newly dead crawl up the cliff and melt in the light of the moon. There are days when spirits peek into my window before rising up. Occasionally, they hang by the window and speak with me. They ask about what I do, and those that know me want to know when I am going back to college. But these conversations are always one sided and no matter how loudly I speak they don’t seem to listen. They just keep speaking.

One afternoon I decided that instead of suffering the torments of his image, I should rather go and talk to the man straight. And after I had my snack I went straight to his shop. He was sitting idle. It looked as if he had sold all his pigeons except for that yellow one. He recognized me and said, “You were supposed to go back to your college?”

“I couldn’t due to rain,” I said.

“Oh yes. How many days they say it will take to clean the road?” he asked.

“I don’t know. A week may be,” I replied.

“These people are very lazy,” he said and looked away.

He asked, as if he didn’t know what I wanted, if he could help me in any way possible. When I told him about my dreams and my views on previous births, he half agreed. But when I insisted on telling me about him he got very angry and scolded me to leave the place at once. He said he was going to shut his shop for the day because there was no business and if customers came, he had nothing but his yellow pigeon to sell. I knew he was faking. It was not even evening yet. I looked around the market but hardly anyone was around. During afternoons, shopkeepers of the market usually go for their siesta and come back two or three hours before evening. I looked at my watch and to my great surprise the needles had halted at 2 o’clock.

I checked the clock tower to confirm the time but it too was showing the same time. While the pigeon seller was pulling his racks and cages inside his shop, I calculated that when I left the house to come here it was 2 o’clock. As far as I could remember I had already had a fairly long conversation with him. I persuaded myself that I might have seen the wrong time. But then I remembered that while I was coming here a villager had asked me the time and I had told him it was 2.15. Had I seen the wrong time, the watch could not have run for 15 minutes. And if it had run that much, how could it go back again to two and get stuck there. While I was thinking, the man had already closed his shop and hung the pigeon cage to his cycle bar. He didn’t reply to my goodbye. I came back.

The road didn’t open that week and the pigeon seller didn’t return to his shop. I enquired around, but nobody knew where he lived.

“He just comes and goes. He never talks to anyone,” a woman, in her mid-twenties, told me. She said pigeons were hard to catch and it was possible that the man had not come to his shop because he had none to sell.

Later, the same day, I met my cousin along the road and he told me that our maternal uncle had come and he was looking for me. I was glad at the news for my mama was fun to have around. He was the youngest of my mother’s siblings and had been to Saudi Arabia for work. He told us many stories about his work of herding sheep in the desert. For many weeks he would remain in the desert with only sheep for company. Then a big truck would come and take them to another place. On Eid the sheep were sold and he was given a month off along with a fat bundle of money. He worked in Saudi for five years and then came back, married and never returned.

That day mama said that he had brought me a gift. To my shock he had brought with him the yellow pigeon.

Petrified, I asked where he found the pigeon. He said that he had bought it from the bird seller in the market. That couldn’t be true, I told him. The shopkeeper had been absent for many days now. But uncle was sure and he even invited me to come to the market and see the opened shop with my own eyes. Not wanting to carry on the argument, I changed the subject. Uncle told me that the pigeon was not exactly a pigeon but a rare kind of parrot which were now thought to be extinct. I didn’t agree for the beak was not that of a parrot.

I decided to wash the pigeon to see if the color was natural. Uncle, always ready to experiment, quickly agreed. The color was actually true. As the pigeon was drying itself in the sunlight, I asked uncle why I felt as if I knew the bird seller.

“Oh he! He is such a genuine fraud,” uncle said as if he was imagining something funny.

“Genuine fraud?” I was clueless.

“It is that he is always changing professions. Sometimes he is selling kafal, at other times he is a pundit and yes occasionally a lama.”

Then he paused a little as if getting into something and said, “You know what? Once when he was a lama, he tried to exorcise Baroodkhan’s ghost from your grandfather’s body.”

“Yes, it was him!” I exclaimed.

“But you know, bhanja?”

“What?” I asked.

“The guy is a genius for whatever he does he does genuinely, even when he is cheating people. And if he fails in a job he has undertaken, he never touches it again and never talks about it.”

Vishnu Sharma is fond of ghosts and loves hearing about them from the people who live with them. He is also a journalist based in Delhi.

This is a beautiful, eerie, and deeply layered short story, The Yellow Pigeon reads like a quiet Himalayan folktale told through the lens of magical realism.

LikeLike