Pritha Mahanti

Welcome to Rough Cut Republic, a series where we look at films chronicling the quiet heartbreaks and loud ironies of a nation busy erasing its past while feverishly scripting its future in unpalatable shades of saffron. Each documentary in this lineup unpacks what it means to belong, to remember, to resist and to simply exist in a country that is increasingly bending under an insecure establishment. From bedtime stories curdled into propaganda to railway tracks that no longer run through common ground, these films capture a new republic in the making—cowardly, confused and communal. Rough Cut Republic is a series that gives a glimpse into India reimagined, recoloured and rebranded—a place where forgetting is policy and remembering is protest. In this third and last part of the series we look at No Space to Pray and On the Right Track, two films that explore how the public domain is shrinking into a space meant for those wearing the right colours, chanting the right slogans, and calling the right gods.

Expanding Roads, Shrinking Nation

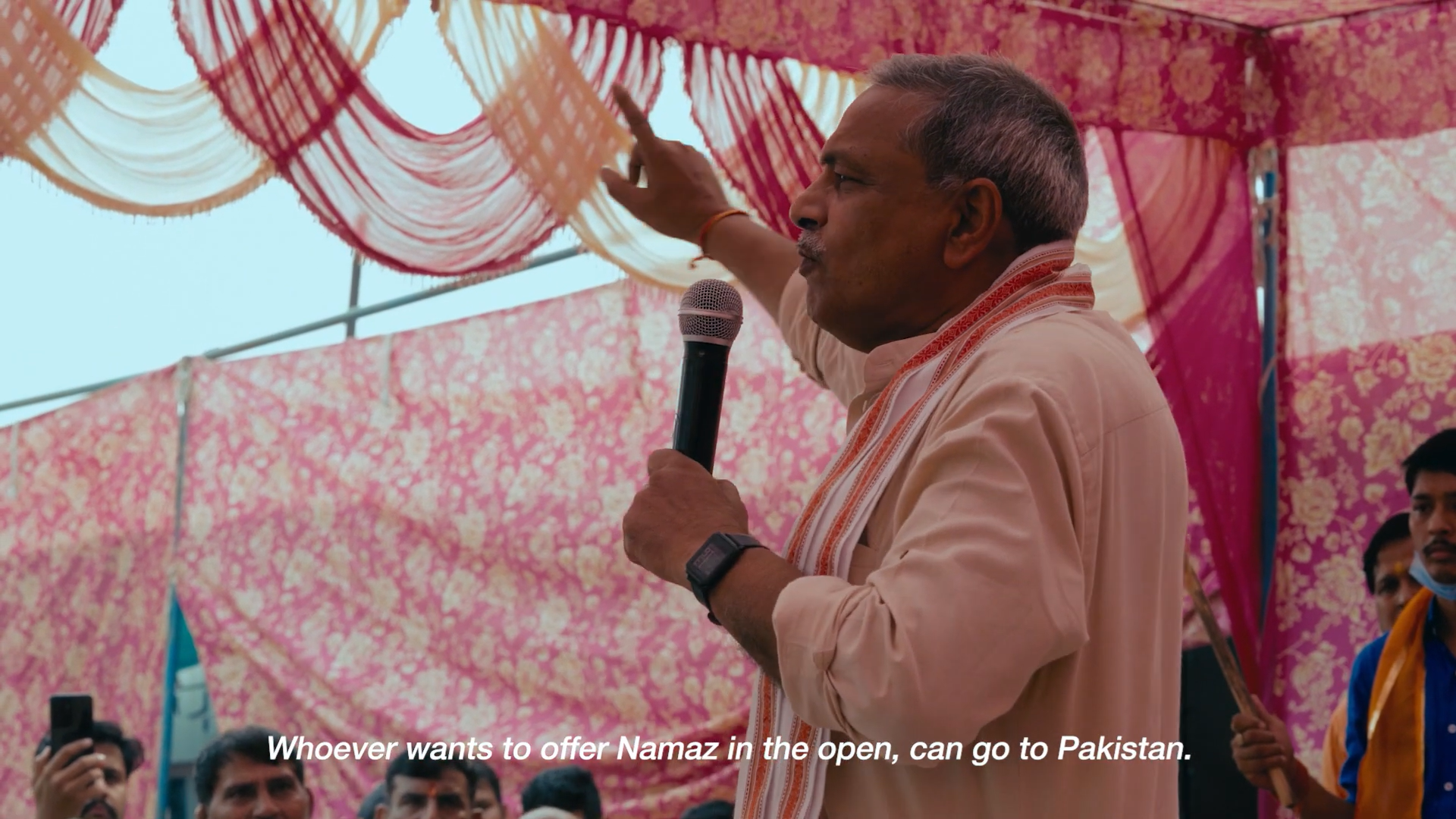

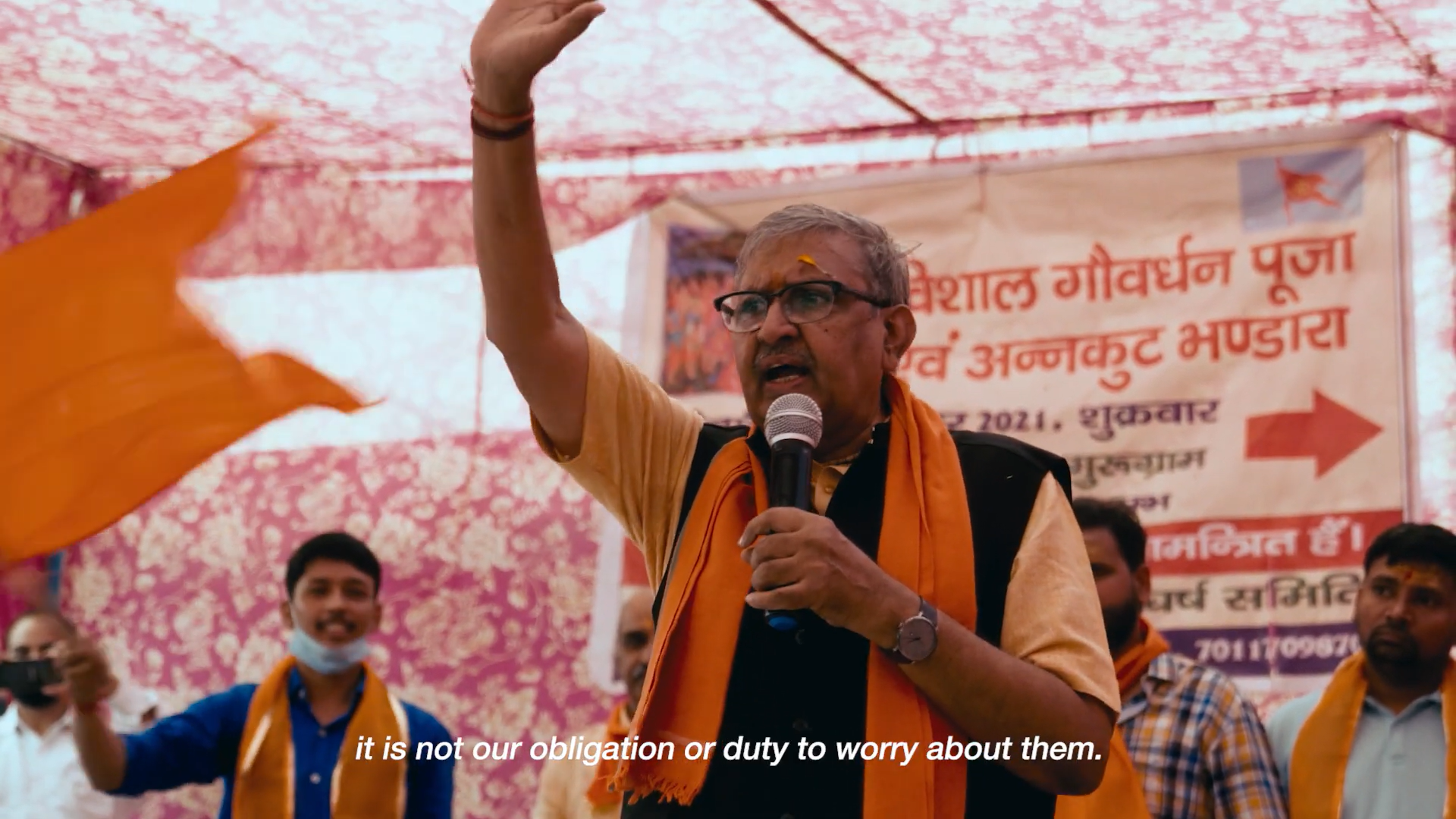

Stills from ‘No Space to Pray’ (left) and ‘On the Right Track’ (right).

On the morning of August 15 this year, I was on my way to meet a friend. Just a lane away from my house, I passed a puja pandal—unmistakably a BJP event with party flags fluttering in the air. While my guess was that the deity would be Ram, the choicest god of the hour, it was Bharat Mata instead. Further into the city, Kanwar processions clogged the roads with jarring devotional remixes, uncouth groups of men (read devotees) hooting and shrieking at passersby, and ‘Jai Shree Ram’ chants piercing the air. On my way back home in the evening, I found myself stuck behind yet another procession. I watched it grow louder and more frenzied as it approached a mosque at the crossing. Civic police stood by, some smiling, barely able to hold back their cheer. Some pedestrians and commuters, although visibly impatient, dared not express their irritability. As the rickshaw I was in finally pulled away from the crowd, I sank into my seat. In this secular republic, what was once a day to celebrate freedom and democratic ideals, had morphed into yet another festival of the majority. In this ritualistic spectacle of nationalism a new public order asserted itself—loud, saffron, and unashamed.

A similar but quiet saffronising plays out in On the Right Track, a documentary that captures the changing ethos of Mumbai’s railway ecosystem. In one scene, Republic Day is marked at Chunabhatti station with the ceremonial hoisting of the tricolour and performances by a group of school children. But the celebration doesn’t end with the distribution of sweets and snacks. Inside the station manager’s office, a Satyanarayan puja is underway. The manager, a recent appointee, explains that she initiated the ritual the previous year to ward off the bad luck believed to cause accidents at the crossing. This blending of state duty and religious custom is certainly not new. Hindu worship has been so embedded in the rhythms of public life that its presence on a national occasion seems almost unremarkable. Yet one is left to wonder: would a station manager from a minority community have the same discretion to bring faith into the office?

Namaz underway amidst protests in Sector 37, Gurugram, in No Space to Pray.

In No Space to Pray, this asymmetry of religious expression curdles into open hostility. At a designated Friday namaz site in Gurugram’s Sector 37, the now familiar spectacle plays out. Members of various Hindu extremist groups gather hours before the namaz, staking claim to the space with slogans, saffron flags and loud proclamations of securing public spaces from religious gatherings. The infamous sentiment of ‘Hindu khatre mei hai’ (Hindus are in danger) informs the crowd. ‘This is our land’, ‘let them go to Pakistan to offer namaz’ and other communal tirades ensue; rage dressed up as civic concern. Yet the targeted intimidation is unmistakable. As Shehzad Khan of the Muslim Ekta Manch arrives with fellow worshippers, the slogans and threats grow fiercer. The heavily deployed police finally steps in. A few agitators are loaded into detention vans, almost as a matter of appearance than accountability. Amidst this disturbance, the namaz proceeds, contained and composed. The contrast couldn’t be more glaring; a Hindu ritual inside a state office becomes a cultural act while a regular namaz in the open is a law and order situation. In the heart of NCR, one of India’s touted urban centers, religion becomes a test of what the majority can display and what the minority must apologise for.

Shots from Mumbai locals in On the Right Track.

This narrowing of who gets to occupy public space isn’t just about prayer sites or performative religiosity masquerading as nationalist spectacle. It works insidiously through the mundane and everyday, as On the Right Track demonstrates. Made by a group of students—Devashish Shukla, Sam Venkat, Isha Tomar, Niv, Rituraj and Sameer Ahmed—at TISS Mumbai as part of their thesis project, the film was originally envisioned as a nostalgic exploration of bookstalls at railway stations; those familiar corners where travellers once grabbed a Champak or an Amar Chitra Katha before a train ride. As the film opens with snapshots of the more than familiar sights on a local train commute with a background music that plays on the fantastical, you start getting comfortable on your seat. We are then introduced to Jayprakash Govind Shetye, the manager of Sarvodaya Sat-Sahitya Book Stall at Mumbai Central. He explains his association with the Adivasi Gram Seva Sangh, a charitable organisation which uses the proceeds from the book sales towards social service. As he speaks of his labour of love post retirement, it’s hard not to miss some selected books on display, predominantly those on spirituality, nationhood and self-help. Jayprakash boasts of the “good” collection of books that surround him, emphasizing that one would not be able to find any “vulgar” book at his stall. When asked about the availability of crime thrillers, he scoops them out from under the table, as if from a restricted section. Gone are the days when pulp fiction, detective thrillers and comics graced a sizable section of an A.H. Wheeler stall. The drop in sales post the Covid lockdown changed the character of these stalls altogether. Railway board stipulated that all such outlets be converted into multi-purpose stalls. As book and magazine covers receded behind a plethora of miscellaneous items, from food to medicine, so did a slice of the history of railways in India. Vivek, another stall manager at Chunabhatti, also states with a quiet resignation how “wafers” have replaced “papers”. His little newspaper shop is now overrun with munchies and soft drinks. But like Jayprakash, Vivek holds his life at the railways dearly. Having worked at the stall for close to four decades, he is in tune with every rhythm and texture of the world around the tracks.

It is not until the halfway mark that the film shifts in tone to indicate the much larger transformation at play. At the end of the Satyanarayan puja scene described earlier, when the station staff gather for a group picture, the manager calls out to someone called Abdul to join. As a visibly shy Abdul fidgets in his position, the manager asks “Why are you so tense?” Almost like a premonition, the scene dissolves into a black screen and the sound of a bhajan surfaces. As it gains tempo, we are drawn into a kaleidoscopic shot of passing overhead lines and fragments of the city. This is when you start being uncomfortable in your seat. A group of working-class commuters on a train breaking into spontaneous bhajans, although not new, now evokes a certain unease. The question looms: who gets to narrate culture, and who must quietly travel through it?

The kaleidoscopic shot in On the Right Track.

For the makers of On the Right Track, the politics of assertion and erasure was not hard to dig out. It presented itself in the near-constant surveillance that the crew was under while filming—in one case even facing detention. Furthermore, the growing fervour around the Ram Mandir inauguration and protests across Mumbai for Maratha reservations made the atmosphere more volatile. In one striking scene, a group of protestors is seen assaulting a commuter on the platform while raising slogans of ‘Jai Shivaji’ and ‘Jai Maratha’. The on-screen text explains: the commuter had simply unplugged a phone charger that belonged to one of the protestors. From bookstalls becoming sites of ideological sanitation to gatekeepers of majoritarian pride making a spectacle of violence, the reshaping of public consciousness is well and truly underway.

It is, however, in No Space to Pray, that the sheer brutality and disturbing assertion of fundamentalist majoritarianism is brought to the fore. The film opens with a congregation of radical Hindu outfits and their supporters for Govardhan puja at Sector 12, Gurugram, one of the few remaining designated Namaz sites. In this rapidly expanding satellite city of the national capital, open spaces for Muslims to pray together has seen a sharp decline. From over 100 spots where namaz would be offered with the permission of the district administration, the number dropped to 20 in 2018. At Sector 12, as we see, this is not merely a festive gathering, but a show of strength; of the might and impunity of those who think they ‘rightfully belong’. The speeches that follow are proof. Surendra Jain, General Secretary of the notorious Vishwa Hindu Parishad declares that no inch of public space be given for namaz. His reasoning is as vile and predictable as most venom spewing Hindus have made it to be—the association of namaz with jihad and terrorism and Pakistan, the handful of words that exist in their dictionary of hate. Mahavir Bharadwaj, President of Samyukta Hindu Sangharsh Samiti (an umbrella outfit of 22 right-wing groups) goes a step further to shun any idea of collective happiness in favour of the sole well being of Hindus. His mockery of worshippers offering namaz as some ‘creatures’ that are undeserving of sympathy calls to mind the unsettling association one finds in Holocaust literature where the term “muselman” or “muslim” is associated with the most dehumanized victims of the Nazi concentration camps. The reduction of the word ‘Muslim’ to some absolute markers of abject life only reinforces the targeted attacks by structures of majoritarian control.

Stills from No Space to Pray.

By embedding themselves within these unfolding events, filmmakers Raunaq Chopra and Devanshi Yadav not only capture the hostility of organised mobs, but also the routine normalization of hate through the violence of speech. The chorus of intimidation with which they shout down any voice of reconciliation only demonstrates that the idea of ‘no space to pray’ bleeds into the larger fear that there is increasingly ‘no space to be’. Even in the distant detached aerial shot of a sprawling and spotless Gurugram, the sense of suffocation is tormentingly palpable. While Muslim activists languish in jail for articulating a political vocabulary for resistance, majoritarian voices cloak incitement as ‘free speech’, enjoying both state tolerance and media amplification. This rhetorical impunity begs a deeper legal and moral reckoning: is hate speech free speech? Is their convergence and distinction only a matter of convenience for the prejudiced judiciary? Supreme Court Advocate Shahrukh Alam’s observation cuts through the noise. She says,

Hate speech is not episodic but rather systemic and accumulative—[….]which always presumes a lesser right for Muslims to be in India—manifest in various, more direct ways now—in speech and in action. The idea that Muslims can be asked to leave the ‘Dev Bhoomi’ of Uttarakhand, for instance, or a particular district or village of the state, derives from that cumulative effect of the idea that presumes lesser rights for Muslim citizens; the belief that they do not really belong here, but in Pakistan. It is not sudden or episodic. It is systemic and cumulative.

The film lays bare this continuum.

An authoritarian establishment, animated by the markers of fascism, thrives on sameness. Societies fed on totalitarian ideologies do not merely suppress dissent; they erase differences. In On The Right Track, this pursuit of uniformity becomes visible in the aesthetic flattening of public space: identical shelves, identical covers, identical gods. Bookstalls that once carried the pulse of the travelling public—pulp fiction, paperbacks, political magazines—are now uniform and uninviting. Vivek’s decades-long association with his modest stall, cannot withstand the economic violence of corporatisation. Fast food chains and high-rent expectations have started taking over what these men built through years of slow, attentive labour. In Gurugram—poster city of India’s IT sector—the transformation of open, communal spaces into battlegrounds of exclusion is not an aberration, but a chapter from the same playbook of corporate-Hindutva alliance. One recalls how Muslim-owned eateries bore the brunt during the Kanwar processions when devotees reportedly refused food from “impure” hands. In an economy in freefall, the scapegoating of minorities becomes both an absurd theatre and a convenient distraction. Yet it continues, upheld by the casual collusion of state machinery. The image that lingers is damning in its clarity: a police constable, gently patting a Hindu agitator on the back after disrupting namaz.