Pritha Mahanti

Welcome to Rough Cut Republic, a series where we look at films chronicling the quiet heartbreaks and loud ironies of a nation busy erasing its past while feverishly scripting its future in unpalatable shades of saffron. Each documentary in this lineup unpacks what it means to belong, to remember, to resist and to simply exist in a country that is increasingly bending under an insecure establishment. From bedtime stories curdled into propaganda to railway tracks that no longer run through common ground, these films capture a new republic in the making—cowardly, confused and communal. Rough Cut Republic is a series that gives a glimpse into India reimagined, recoloured and rebranded—a place where forgetting is policy and remembering is protest. In this second part of the series we look at sambhal ke and Insides and Outsides, where the ‘I’ of the individual wrestles with the ‘I’ of India.

India Through the ‘I’

Six years ago, a winter afternoon in Delhi changed something in me fundamentally. This was my favourite season in a city I was inexplicably fond of. But on that particular afternoon, the smell of a burnt neighbourhood in North East Delhi lodged itself in my memory in a way I could never escape. As the auto drove past charred houses and shops, I lost the will to document any of it beyond a few clicks. We were going to meet a family that was lucky to be alive. When I stepped out of the auto, I was standing before what I saw of the nation at that very moment. The inside of a mosque looked like a pitch black cavity. I could only make out the skeleton of a ceiling fan hanging precariously against its will. Adjacent to the mosque was a small Hindu temple; its floor freshly washed and the altar decorated with incense and flowers. It seemed like a dystopian loop. Twenty eight years ago, a dome of a medieval mosque was razed to the ground. Perhaps for the first time in my life I was dwelling on my surname more than ever. That was a luxury.

What does it mean to belong to a nation that always tries to bracket one as the ‘other’, either overtly or covertly? What does citizenship even mean when Khalil-ur Rahman, a retired professor from IIT Delhi expresses his reluctance to have a name plate outside his new home? He believes it would invite unnecessary trouble and doesn’t want his home to be marked. His wife, Rubina Rahman, however, doesn’t want to hide her identity. While this argument is on, we see Khalil, Rubina and their son Arbab Ahmad huddled over an album. This is how Arbab’s film Insides and Outsides ends—a deep anxiety and fear betraying the picture of cozy domesticity. In sambhal ke, the same fear is writ large on Shalini’s* face as her daughter Lubnah Ansari films her at a restaurant in the UAE. Over coffee and snacks, Shalini tears up as she argues against Lubnah’s insistence on returning to India. When her daughter says, “I am half Hindu”, Shalini promptly responds, “So what?…Your half Hindu identity is hided by your half Muslim identity”. These are peacetime conversations.

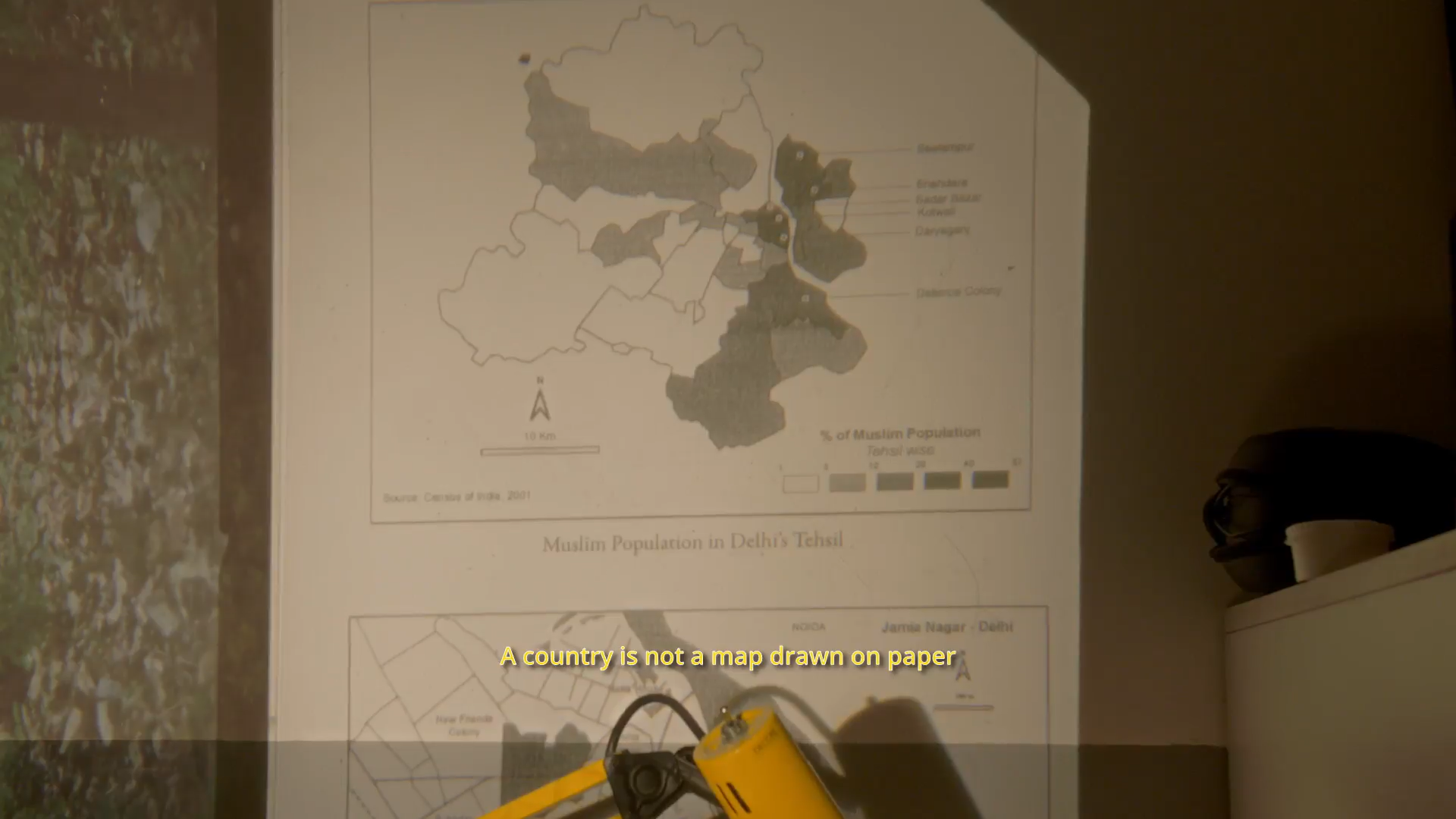

In both Insides and Outsides and sambhal ke, the filmmakers turn their lens on the space they grew up in. Although both Arbab and Lubnah have been documenting this familial space for years, the camera now appears somewhat like an arbitrator for the many old and new unresolved questions around their sense of being. For Arbab, the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) and National Register of Citizens (NRC) became a watershed moment to reflect on the many intricacies of growing up as a Muslim in India. Unable to keep his lived experience outside the ambit of his research, Arbab set out to contextualise his life through a film that interlaces the socio-political and the private. For Lubnah, similarly, a thesis on how women negotiate selfhood and identity in a Hindu-Muslim marriage, took her closer to her interfaith home. In both films we see a self trying to situate itself in a nation that has always been ambivalent about its outlook and approach to Islam. They are also a mindmap of the hyperconsciousness and hypervigilance around one’s identity in a democracy where the tyranny of majoritarianism, while being a permanent fixture, has now taken a ghastly and grotesque form.

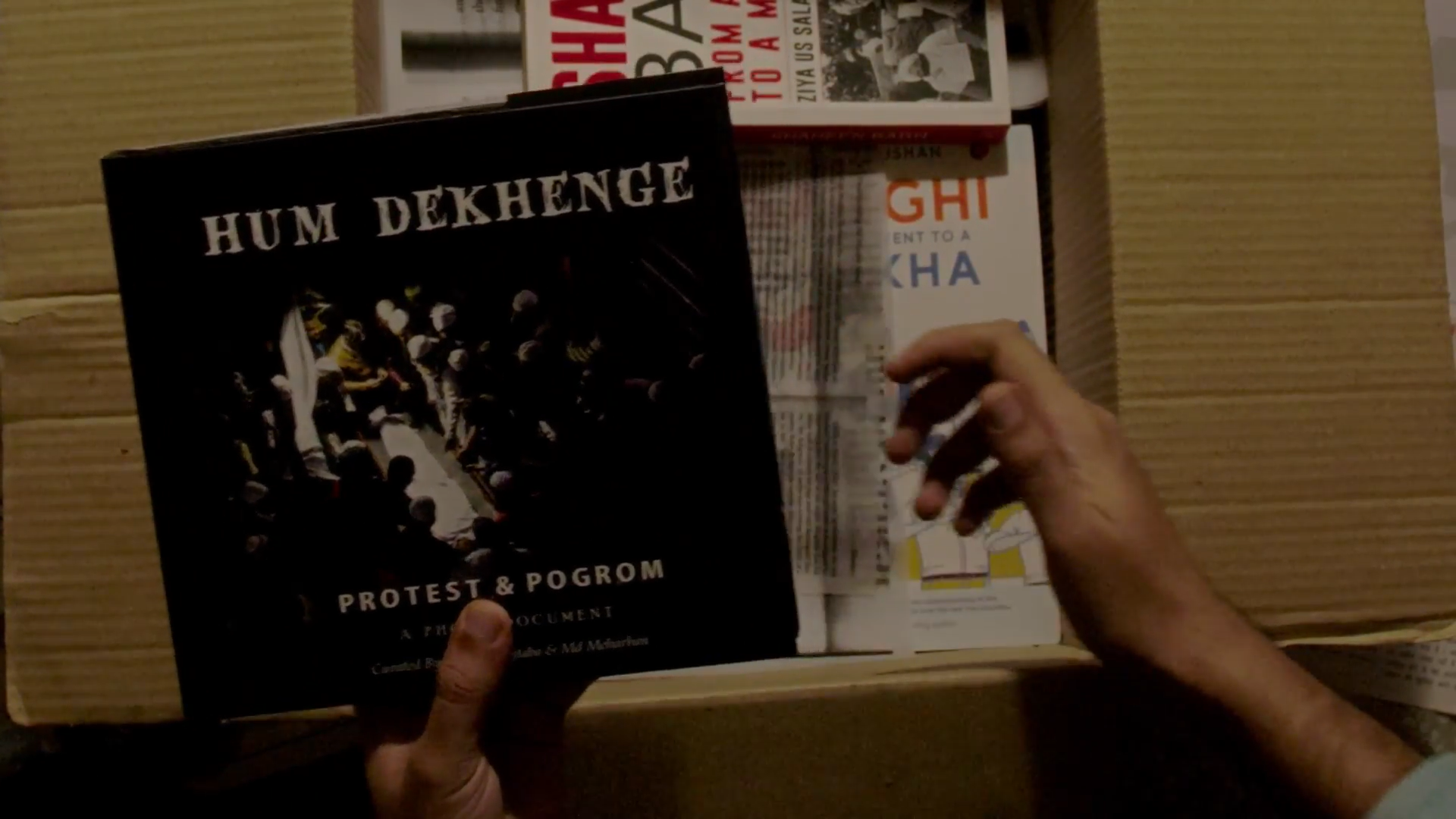

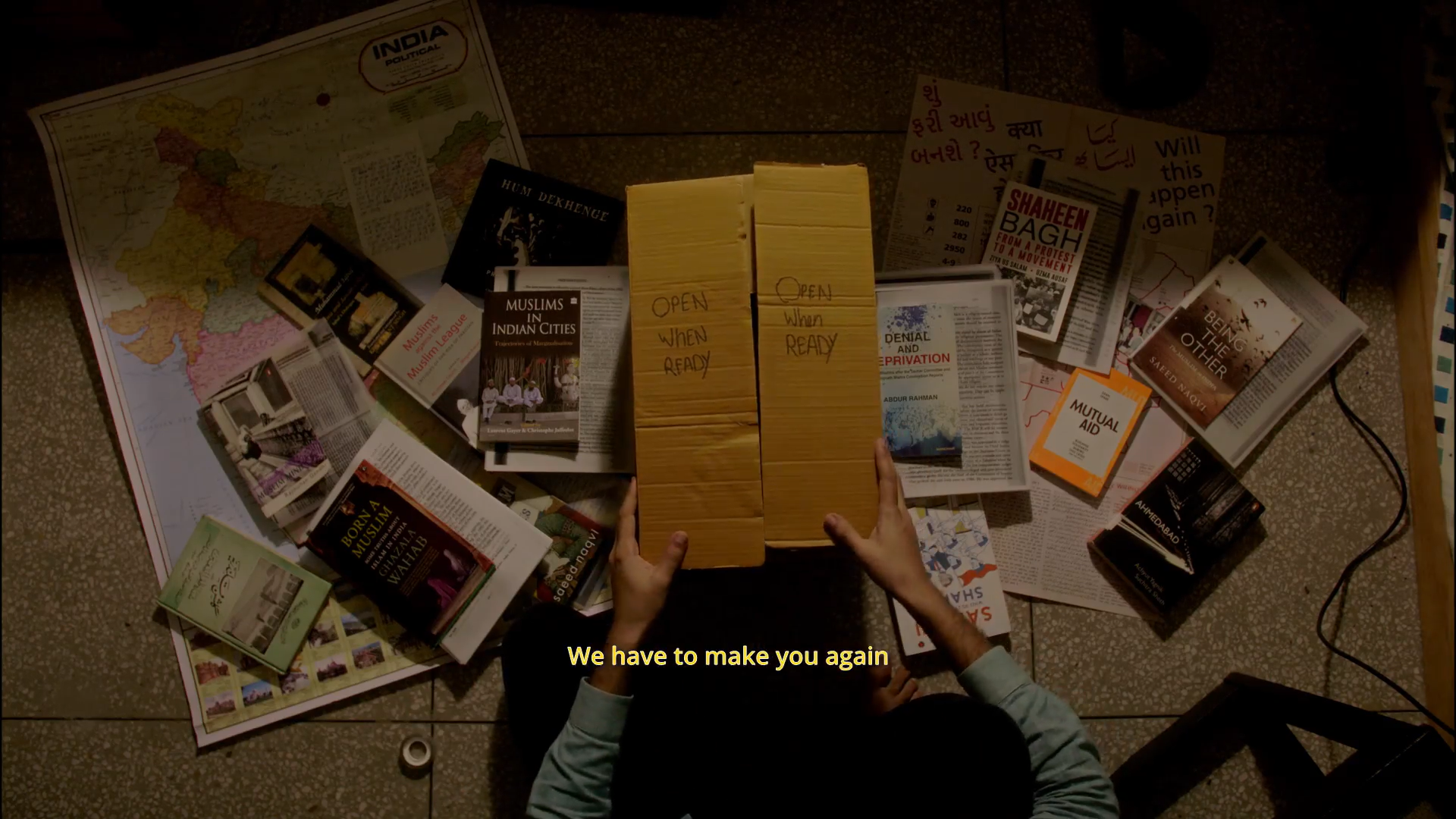

In his poem ‘What is Home?’ the Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha speaks of the many things that sum up a home for him, until he is confronted by a child who asks “Can a four-letter word hold all of these?” In this moment of aporia, we realise that a word might be breaking at its seams with the weight of its meaning. In Insides and Outsides too we witness a struggle to contain the messiness of what a home might signify. Arbab begins his film with a series of staccato shots—the protests against CAA NRC, archival footage and home videos—that together gesture towards the Muslim experience in India, leading to a scene where he opens a carton stacked with books, maps and family photographs. He welcomes us to the ‘end of history’, a phrase that marks the demise of a once familiar world. The protagonist, Arbab himself, is caught in a limbo of loss.

As he takes out the contents of the carton, the rapid cutting rhythm continues to include the materials he had collected in the years between 2019, when the country erupted in furor against CAA, and 2022 when it was crippled by a pandemic that gave a new boost to Islamophobia. The pandemic soon became a smokescreen of a deeper, more persistent malaise. The humanitarian crisis that unfolded during this time had more to do with repressive regimes, police brutality, lopsided government policies and a toxic political opportunism that was ready to put at stake the lives of all those beyond the ambit of its agenda. For Arbab, this was a time of introspection; a re-look at his life and that of others in his tribe. In Insides and Outsides, we are invited to imagine the protagonist anew; to release him from the limbo. And as a start Arbab delves into the idea of home, a word that he shows to be deeply entangled with movement. In his first short note on moving, Arbab explores the question: “why do we move?”

Arbab’s exploration of the idea of movement begins in the lives of his parents. Their experiences offer two distinct, yet intertwined narratives. His mother, as he says, was almost born in transit. As a child she never stayed at one place for more than two years. Amidst this constant shifting of homes, the only anchor she found was in her family. Later in the film when she reflects on what home means to her, it is the people she can call her own. Her memory quietly pushes back against forces that often render women’s histories invisible. For a Muslim woman in India, this threat of erasure becomes doubly potent. But Rubina Rahman refuses to be written out. She holds on to her stories and insists everyone should be allowed to hold on to their own. For Arbab’s father, movement was driven by a dream of progress and possibility in a newly independent nation. In 1979 he joined IIT which became his home for the next forty years. In the film, however, we see him in transit to a life post-retirement. His new home, away from the campus, in a majority Hindu neighbourhood demands negotiation, proof and caution.

Movement, Arbab comes to realise, is not as simple and linear as it must have been for his parents. Footage and photographs of the targeted anti-Muslim violence in North East Delhi suggests that the answer is far from simple. While for his parents movement was shaped by aspiration or familial ties, for a large section of India’s persecuted minorities movement has often meant displacement under duress. Arbab describes the CAA as “another addition to the saga of movement”, while framing the widespread protests against it as the collective insistence and assertion on the right to stay. A year later, in the midst of the pandemic, Arbab pens his second note on moving while we see him pack his belongings and return to his parents’. Though the idea of home represents “comfort and safety”, he acknowledges that these cannot protect one from the world outside. “You are left” he says, “in the slowly shrinking safety and comfort of inside”. As we see shots of migrant labourers stranded on the roads—forgotten in a nationwide lockdown—waiting endlessly for transport, Arbab tells us, “no one likes moving, no one likes changing home. Let us not romanticize new beginnings.” The theme of home and movement runs through the rest of the film which chronicles the shift that his family goes through, both spatially and emotionally as his father packs up life post retirement, negotiating what it means to begin anew in a country where even belonging feels precarious.

In sambhal ke too, Lubnah navigates the layered messiness of home, moving between geographies and generations. She traces the finer contours of an interfaith marriage across the families involved, choosing to steer clear of what she describes as the two dominant tropes that such unions often fall into—either an over-romanticization or the depiction of spectacular violence. sambhal ke as it translates, is a careful and measured attempt to grapple with a complexity that doesn’t lend itself easily to reason. It is also, in some ways, a self indulgence—a whisper to oneself and to others, ‘be careful where you tread’. The fault lines of hurt and prejudice in families still struggling to accept an interfaith union is revealed in moments both subtle and explicit: when Lubnah’s question to her grandmother on what she’d like to document in a film about her family goes unanswered; when her uncle compares intercaste or interfaith marriages to a car that cannot run smoothly with mismatched parts; or even in a friendly banter where Lubnah’s parents resort to stereotypes about identities while teasing each other. The film also gently unpacks the dynamics that kids bring into such marriages. Lubnah says it is a space where family not only begins to open up, but also to indoctrinate. For example when her uncle advises her to study the Quran and to accept Allah as the only true God or when her grandmother admits that any marriage outside the community weighs disproportionately on the wife. For Lubnah, therefore, home is a spillover of many beings and modes of belonging; a careful reckoning with the past where some family albums are strictly kept out of reach for fear of reigniting old grievances.

In a nation where interfaith couples often face relentless legal and existential ordeals, Lubnah’s parents found solace abroad, far away from the din and shadow of a state that threatens to erase such unions. Despite the lingering disaccord following the drama around their marriage, they have been living without dwelling too much on the past. Lubnah says it was necessary to find a language for the emotions in the family and to hold them in a space beyond her own body. The homemade documentary, therefore, becomes a vessel for the many fragments of the personal that she tries to contend with. Although the strongest thread of enquiry is around her own family, Lubnah brings in two other women who married outside their community and faced estrangement from their families. As her Hindu sister-in-law reads out a copy of the police report that her family had filed after she eloped, she chuckles at the phrase that says she was led astray by the man, when in fact it was a mutual decision. The scene echoes the undercurrents of the ‘love jihad’ conspiracy theory that has, of late, consumed the nation, where interfaith love is recast as manipulation and coercion, especially when a Muslim man is involved. This scene reveals the quieter devastations that such propaganda leaves in its wake.

Another voice that weaves through the film is Lamya’s*, mother of Lubnah’s friends Mira* and Kaira*. She speaks of her quiet constancy of faith that remains unshaken, even as familial ties frayed. Be it chanting Shivoham or reciting the Durood Shareef, Lamya finds a refuge in spirituality that keeps her anchored. The weight of her words is felt in the next scene when Mira, in response to Lubnah’s question on what her own film on her family might explore, talks about the unequal struggle that both binds her parents together and marks the difference in their journeys. “My dad, from a Hindu family, did not have to face half as much of a struggle as my mom did”, she says. These moments reveal the emotional labour women continue to shoulder as they negotiate love, marriage and freedom in a society and nation hardwired to uphold patriarchal and communal boundaries.

These layered selves of belief, resistance, care and conflict, continue to unfold in Lubnah’s own encounter with her family. In a scene that sharply departs from the rest of the film’s tone, she gathers her father and four uncles to ask them a deceptively simple question: “what makes a good family?” We expect a debate but what follows is far more revealing. As each of her uncles begin to speak, Lubnah splits the frame into four quadrants, their voices bleeding into one another, forming an indistinct hum of opinions. In the jumbled chorus we can only catch stray phrases about spousal duties, balance of secular and religious education, values etc. For Lubnah, this rupture was her own way of seeking catharsis. “I was tired of debating them in the way that I was debating them”, she admits. She lets her edit convey the frustration with their statements while at the same time playfully exposing their inadequacy by pushing them into a dissonant soundscape. When she returns to the single frame, she tells them they missed out on an important element: love.

Yet this catharsis is complicated by the larger political landscape in which her film circulates. The vilification of Muslim men in India has been on the rise with a divisive government fuelling majoritarian paranoia. In such a context Lubnah is wary of inadvertently contributing to the rhetoric that already dehumanises the men in her community. “No matter how much I debate with them” she says, “I also care about the men in my family.” But care is not absolution. It is about insisting on the full humanity of those whose views she may not share. It is about holding a space for nuance and opposition even in love and solidarity. But Lubnah wonders if a film like this, with its layered portrayal of interfaith kinship and intra-family tension, can be held with the care that it demands. How does one tell a story that implicates one’s own, without flattening it into stereotypes?

Inhabiting and negotiating the messy in-between spaces of self, home and the world is fraught with an anxiety that is apparent in both the films. In a telling scene from Insides and Outsides, Arbab records himself reading out headlines of Muslim men lynched by mobs, even as the sound of his mother calling out to him and the banging of the door grows louder and more urgent. The crescendo almost tightens the chest. In sambhal ke, a quieter but similarly haunting moment unfolds in a scene where we see a Hindu devotional video playing on the television as we hear Lubnah’s conversation with her dad. She asks why her grandfather had urged his parents to settle abroad. “You already know why”, her father replies. When asked if he felt bad, he says he didn’t because he knew too well what it was like for interfaith couples in India. At least their family accepted them unlike many who don’t. Acceptance, albeit reluctantly or despite the protestations of relatives, is as good as it gets for couples who marry outside their community.

In both films, however, there are also gentle moments of selfhood. Rubina Rahman laughs and tells her son that she is ready to take any risk for his sake. Lubnah’s father tells her that he simply fell for her mother, the why and how he cannot explain. The ‘I’ in India is inevitable. It continues to endure, resist and redefine itself in small, deeply personal ways.

* Names in sambhal ke have been anonymized due to the unpredictable nature of online circulation and access.