Pritha Mahanti

Welcome to Rough Cut Republic, a series where we look at films chronicling the quiet heartbreaks and loud ironies of a nation busy erasing its past while feverishly scripting its future in unpalatable shades of saffron. Each documentary in this lineup unpacks what it means to belong, to remember, to resist and to simply exist in a country that is increasingly bending under an insecure establishment. From bedtime stories curdled into propaganda to railway tracks that no longer run through common ground, these films capture a new republic in the making—cowardly, confused and communal. Rough Cut Republic is a series that gives a glimpse into India reimagined, recoloured and rebranded—a place where forgetting is policy and remembering is protest.

Dreamscapes of a Broken Republic

We begin this series with Amma ki Katha (My Grandmother’s Tale) and When Pomegranate Turns Grey, stories looping through generations and holding on to memories against a deluge of distorted histories. In these dreamscapes a nation shapes up like a specter of itself, distant and unrecognizable from its oath of origin. Its memory becomes a broken kaleidoscope—a visual and visceral chaos where familiar anchors are lost to the turbulent tides of divisiveness. Remembrance, therefore, becomes at once a risk and redemption. For those left to remember, all manner of linearity and coherence seem redundant. It is only through fragments and silences that one can make sense of what was and what is. Perhaps only a dream would allow one to come to terms with a shape-shifting nation.

For Nehal Vyas and Khurram Muraad such a dream is tied to the stories of their grandmothers. Although their stories are starkly different, together they speak of a nation that has been caught in the confounding trap of its bloodied birth. While Nehal’s amma looked at the world through myth, Khurram’s Gulnar dadi still looks at it through the dreaded word called ‘Action’ (the annexation of Hyderabad post partition). One’s myth and another’s memory flow relentlessly spilling over generations in a land where the utopia of its imagined being and the brutality of its becoming have sustained an enduring conundrum. And it is this conundrum that both films try to grapple with.

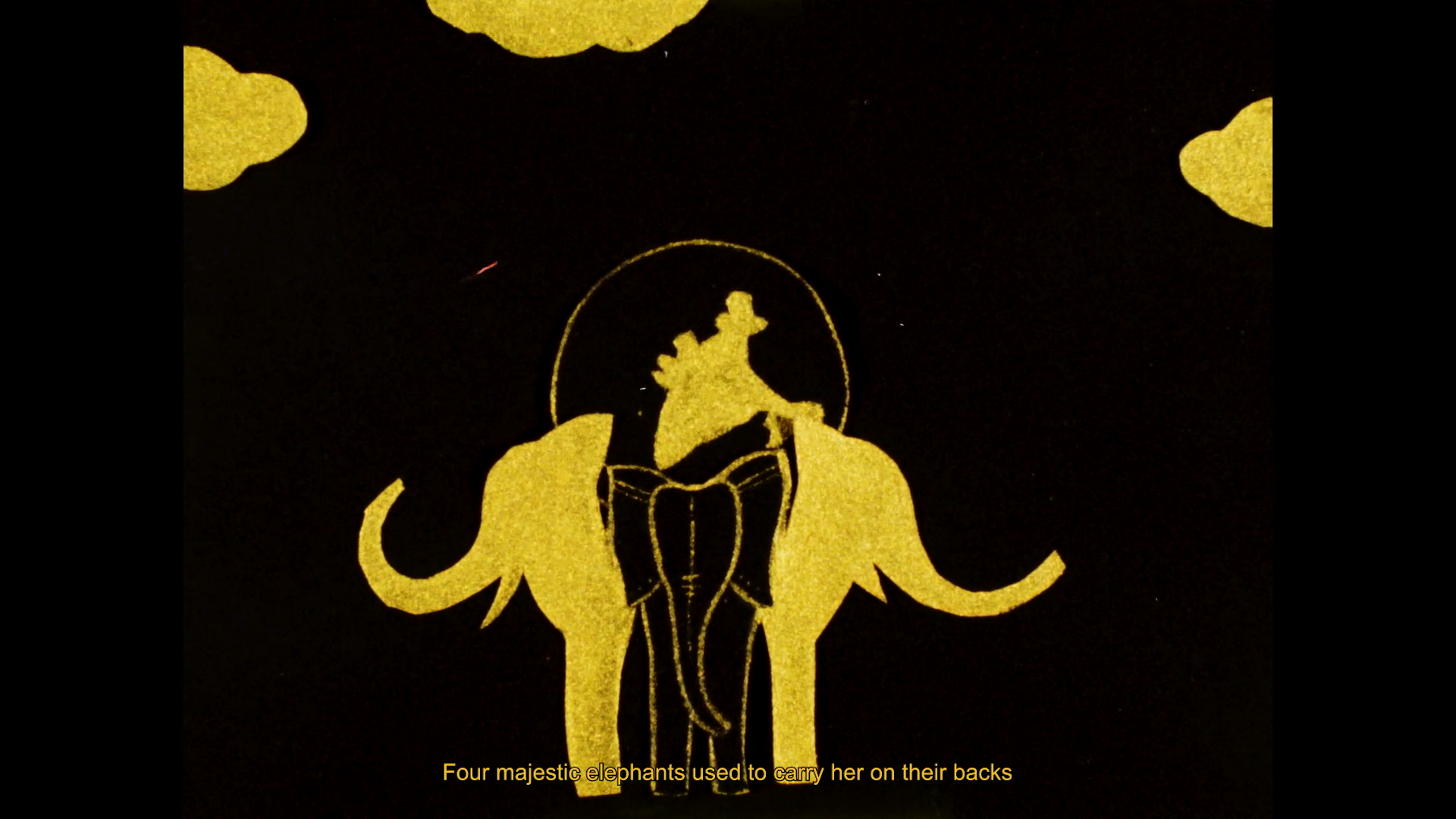

Nehal’s film, Amma Ki Katha, although born out of anger, is a soft whisper that you’d want to hold close, like the many stories and myths that her grandmother told her. The film is a four part dreamscape that looks at the nation through a story of four elephants carrying the world on their backs. They are said to be the chroniclers of everything that has ever happened on earth; custodians of memories passed down through generations, much like Nehal’s amma. In the world of these stories, Nehal knew of gods to be “magical, kind, imaginative and democratic” like the land that had held and nurtured the many cultures and peoples for centuries. But now the contours of this land are being redrawn and the myths remoulded to define who belongs and who doesn’t. In her attempt to hold on to the fading idea of a once familiar world and to come to terms with the fractured myths, Nehal takes recourse to a dream. In it she dives into the memories of each elephant: the first one saw the nation being built, the second heard a myth, the third smelt the fire and the fourth remembered a dream. In its allegorical structure, Amma ki Katha is like a palimpsest of the many pasts and presents that wrestle in the psyche of a nation still unsure of where it is headed.

At its core, the film asks: who becomes the voice of this dream of a nation that is trying to re-remember itself? Through her choice of image making and soundscape, Nehal elevates the mythic quality of the film while rooting it firmly on the everyday occurrences in a republic that has been progressively twisting to the tunes of an aggressive majoritarianism. In the first part of the dream, as we see glimpses of her home city Jaipur, her voiceover reads out the Preamble of the Indian Constitution in Urdu. The choice of language, she says, is an attempt to foreground what is being systematically sidelined. Not long ago Hindi films would feature titles in Hindi, Urdu and English. Somewhere at the turn of the century, Urdu disappeared off screen. Over time, this language has been targeted in many ways, be it the renaming of streets and towns, or curtailing institutional funding or even in attacking brands for using Urdu in their campaign titles.

As the film moves to the second chapter, we witness a re-enactment of a scene from Ramayana where Sita urges Ram to capture the golden deer for her, despite Lakshman’s protestations that it might be a demon in disguise. Nehal grew up with this story—as did many across the country—in various oral forms. For her, Ramayana was not a monolith. In its oral tradition it has been a more democratic and secular text than it gets credit for. Its many re-tellings demonstrate how a myth can be opened up to the imagination. The existence of many Ramayanas is a fascinating example of the cultural fluidity and adaptability of myths to outlive their temporality. AK Ramanujan’s seminal essay “Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas” documents this very plurality. “In India and Southeast Asia, no one ever reads the Rāmāyaṇa or the Mahābhārata for the first time. The stories are there, ‘always already’”, he says. Nehal too grew up with these enchanting and enduring stories until they were twisted in the service of a nation bent on making a hoax out of history. In 2008, after protests by ABVP and a Supreme Court case seeking a ban, Delhi University dropped AK Ramanujan’s essay from its syllabus. Dimwits claimed that the piece was “blasphemous” and undermined the Ramayana’s sacred character. Ram is now a sacrosanct weapon wielded against all those who dare to uphold the idea of a plural India. Amma ki Katha chronicles the dissonance of this disjuncture between the nurturing myths of childhood and the weaponized legends of today.

Khurram’s dreamscapes in When Pomegranate Turns Grey.

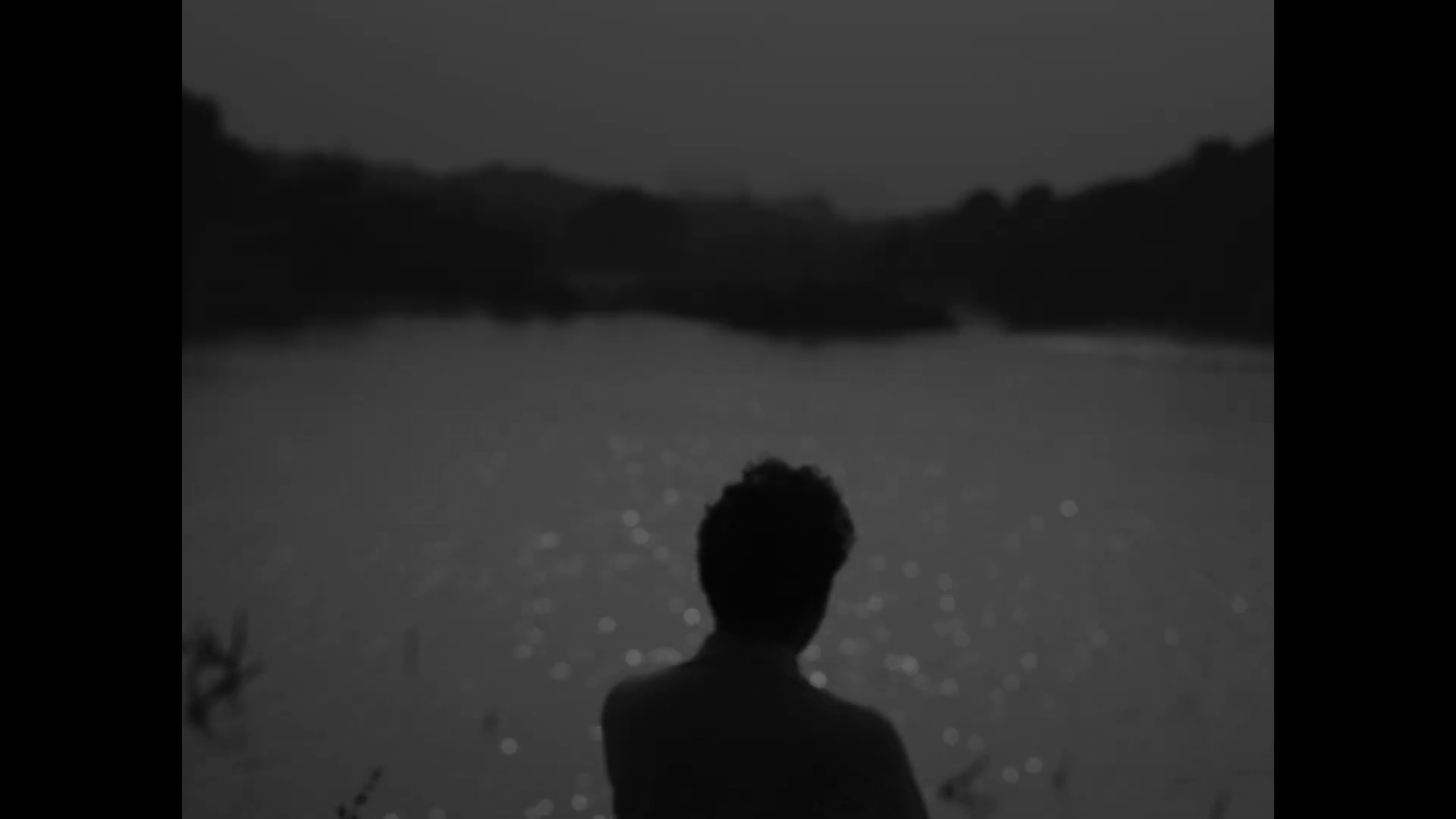

The same conundrum echoes in When Pomegranate Turns Grey. Directors Khurram Muraad and Thoufeeq K attempt to tell a story that has been hiding in plain sight, one that Khurram’s dadi and others in his family have been carrying in their hearts and minds for all these years post independence. The film opens with Khurram’s voice meditating on the weight of inherited silences passed down through generations. As he speaks we enter a black-and-white sequence of dreamlike serenity where Khurram is seen walking through a lush, liminal landscape, following an elderly man whose presence feels spectral, almost ancestral. “We have a rather strange tongue, hiding in the plain words with a singular desire to tell itself”, his voiceover says.

And therefore begins the filmmakers’ retracing of a history that has been reduced to a footnote. The impulse with which they began could have led to a conventional investigative documentary. They travelled extensively across the Deccan, collecting testimonies of survivors of one of post-Independence India’s most violent and least acknowledged episodes. Following Partition, which had already seen nearly half a million people killed in communal carnage, the Indian Army in September of 1948 launched what was termed as “Police Action” to annex the princely state of Hyderabad, then ruled by the feudal Nizam who had refused to join the Indian Union. Though the military campaign ended in swift surrender, it unleashed widespread retaliatory violence against Muslim civilians involving killings, lootings and rapes. An inquiry led by Pandit Sunderlal, commissioned by Prime Minister Nehru, estimated that between 27,000 and 40,000 Muslims were killed—often with the involvement or silent complicity of Indian soldiers and local Hindu mobs. The resulting Sunderlal Committee Report submitted in 1949 was quietly buried and was only declassified in 2013. While the terror unleashed by the Razakar militia is well remembered, the massacre of Muslims remains largely absent from history textbooks, state archives, and public discourse.

However, When Pomegranate Turns Grey refuses to take the shape of an exposé. Instead, it leans into the dissonance of remembering what has been methodically erased. The filmmakers take us straight to its living core. We are introduced to Gulnar dadi—a woman named after the pomegranate blossom, and whose very name carries an oxymoron; gul meaning flower; nar meaning fire. At sixteen, she lived through the brutality of the event that tore her from her sisters and left behind a silence she never fully broke. It was during the CAA protests in 2019, that she began to speak of 1948 in fragments—curfewed nights, sudden disappearances, a constant fear. Watching Delhi descend into state-sanctioned violence, she asked if the ‘Action’ was happening all over again. She had already lived through the burden of proving her right to belong—something the CAA once again demanded. Her memories interlace with Khurram’s dreamscape, creating what he calls “an encounter of tragedy and hope on a grotesque plane.” The film, thus, becomes a container of disjointed memories and timelines that bleed into one another. It trades investigation for invocation, where grief is inherited and transformed.

The film was shaped by the differing sensibilities that the two filmmakers brought to the telling. As someone inside the story, Khurram felt an urgent need to speak; to undo decades of silence and omission. Thoufeeq’s understanding, however, was to capture what lay at the heart of this story—the silence that the survivors carried within them. Where one sought to articulate, the other leaned into restraint. Together they arrived at a form that holds both impulses. When Pomegranate Turns Grey is a film where time is not linear—it branches, doubles back and folds into itself. The past seeps into the present embedding itself in language, memory and the body. “We have gathered experiences and time in all of us in different senses,” Khurram reflects, describing a sense of reality that is already ruptured. In tracing this history through his grandmother’s recollections, Khurram resists the state’s erasure with an act of quiet defiance: to remember is not just to look back, but to make visible the rupture that never truly healed.

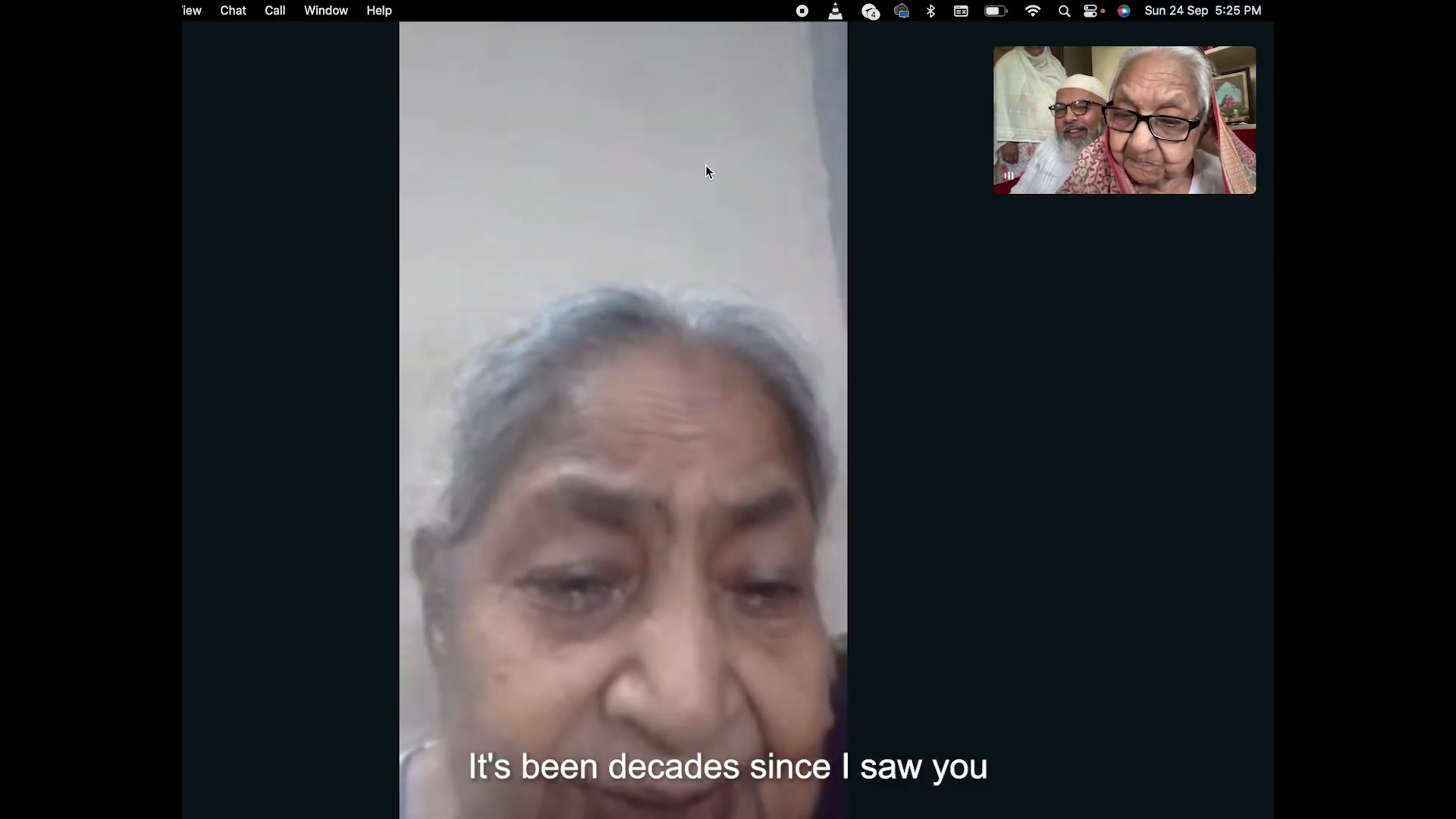

And then comes a moment in the film where all its themes of silence, separation, memory and loss converge into a single hauntingly tender encounter—Gulnar dadi’s virtual reunion with her sister in Pakistan, Noor-un-Nahar. The two had last met when Noor khala had last visited India in the 1980s. Growing up Khurram had always known there was a grandmother in Pakistan, but she existed more as a legend than a person, distant like the estranged neighbour across the border. The weight of Partition and the historical and emotional baggage it left behind rendered Pakistan both impossibly far, yet intimately familiar. It was only during the Covid-induced lockdown, as time slowed and old family ties resurfaced, that Khurram decided to trace that thread. After sifting through a maze of phone numbers passed along by distant and not-so-distant relatives, he was finally able to establish contact.

But history, once again repeated itself. In the aftermath of the Pulwama attack when India descended into another spell of majoritarian frenzy and hostility towards Pakistan intensified, Khurram’s relatives quickly deleted every contact linked to the other side of the border. Khurram remained the only point of contact, which is how he learned that Noor khala passed away in June this year. Thankfully, she had seen the film before she died. What remains is a sobering reminder that Partition was not just a singular event. It is a recurring wound that leaves its mark with every border crisis, every nationalist crescendo and every loss of a shared memory. Noor khala’s letters had dwindled in the years after she moved to Pakistan, likely silenced by the suspicion such correspondence might draw. Over the video call Noor asks Gulnar, “Who is there in Pakistan to call our own?” The question comes from a woman who lived her entire life there and still carried the ache of a home left behind. When Pomegranate Turns Grey becomes, in this moment, more than a film. It is a loop of unresolved trauma, playing out in a republic that continues to fracture under the weight of its omissions.

Stills from Amma ki Katha.

Both Amma ki Katha and When Pomegranate Turns Grey, while deeply responsive to the vicissitudes of a militarised and communal state, resist the urge to portray violence in its most graphic or spectacular form. Instead, they create images that linger with a disquiet. In the third chapter of her film, Nehal films a close-up of a woman in a saffron sari performing Mallakhamba, the traditional sport of gymnastics using a vertical rope. While we marvel at the performer’s fluidity and strength, we are painfully aware of how sports like these have been co-opted by the performative masculinity of Hindutva aesthetics. As the song Dekh Vidhata Tera Naam by The Aavhaan Project plays, the sari wraps and unfurls and morphs into a phytogram of many shades of saffron, each fold burning into the screen like a scar. Saffron is a colour now tinged with dread. Nehal’s image becomes a visual protest against the RSS’s ideal of the fit body as a symbol of national pride, one that masks an unfit mind, unable and unwilling to reckon with the plural, broken, and complex inheritance of the nation. It is here, in this stark visual metaphor, that Nehal allows her anger to find form—not as spectacle, but as searing suggestion.

Stills from When Pomegranate Turns Grey.

Similarly, When Pomegranate Turns Grey never resorts to showing archival footage of the 1948 massacre. Instead, we see a still red pool of water—a silent echo of the blood-soaked river Gulnar dadi speaks of. A lone tree stands in a sea of green grass as Khurram’s uncle recounts his story of being the sole survivor of his family. In an age saturated with the spectacle of violence these films make a powerful departure with their visual grammar. They remind us that silence, too, can scream; that memory, when conjured through absence, can be just as visceral as what is seen.