Pritha Mahanti

As Sohail Ahmed Bhatt stood before a row of five canvases, he could scarcely fathom the ‘art’. Each canvas looked like a blur of lights bleeding into one another, with no discernible form or meaning. This rare foray into a gallery was beginning to weigh on him; it was a crisp winter morning in New Delhi and accompanying a friend to Alliance Française for this exhibition was almost too sudden a plan. However, things took a turn when his eyes landed on the wall text. Artist Namoos Bukhari’s photographic prints weren’t simply the head-scratching contemporary abstractions that Sohail feared he might not understand. They were a haunting visualization of how the world appears to victims of pellet shotgun injuries in Kashmir, the land both Sohail and Bukhari hail from. As he looked at the canvases again, Sohail found a nearly invisible line etched along the black edge– “A Wisp of the Perceptible Vision in a Nutshell“. For him this was new, this was radical. That an artistic display—seemingly illegible at first glance—could jolt a viewer with its context was an experience he hadn’t encountered before. And yet, as he stood before Bukhari’s work, A Secret Visuality of Injustice, he couldn’t shake off the eerie familiarity. The texts, textures, and silences—they mirrored stories he knew all too well. What he was witnessing was their afterlife in art. The exhibition, titled Notes on Omission, carried him further into this reckoning. Moving from Bukhari to nine other works on display, Sohail felt a growing wonder at how these artists had laboured to keep an account of loss. A loss that the minoritised Muslim body often has to face in the many contradictions that lie in making it hypervisible in the media while also invisibilizing it in archival documents.

As her first curatorial project, Najrin Islam’s choice of theme came from a deeply personal place. She had been grappling with the many facets of erasure—sometimes subtle, other times glaring—that one encounters as part of a community perpetually under scrutiny. Be it her parents’ names misspelled in government documents or the casual act of a studio photographer photoshopping a streak of vermillion onto her mother’s hair-parting, these seemingly innocuous acts are somehow embedded in the larger structures of power and prejudice. In 2019, the introduction of India’s citizenship amendment laws brought all of this into sharper focus for Najrin. Right-wing majoritarianism, already on the rise, had now found legal validation. For her and many others, it marked a seismic shift—Islamophobia wasn’t just tolerated anymore; it felt state-sanctioned. In the many conversations we’ve shared as friends, it’s always been clear how deeply this moment impacted her, making her increasingly protective of the cultural markers unique to her faith and now under the threat of erasure. She grew up in a Kolkata neighbourhood where her sense of time was marked by the azaan. It wasn’t just a call to prayer; it was part of the rhythm of life. So, when it was suddenly branded as noise pollution, the attack was as much on religion as it was on the people who kept these practices alive.

Notes on Omission was, in many ways, Najrin’s response to this angst. As she explained, each work in the exhibition acted as a node within a larger network, tracing Muslim cultures across continents and exploring how they are shaped by the socio-cultural forces unique to their geographies. She clarifies that the intention was not to equate the intensity or nature of these experiences across different Muslim communities. It would be wrong to assume that a Bengali Muslim would necessarily have the same experiences as a Kashmiri or an Ahmadi Muslim. Rather, the aim was to acknowledge their distinct histories and respect their heterogeneity while highlighting the common structures of majoritarian aggression they face globally. The exhibition sought to create a space where these varied expressions of resistance could resonate with one another, revealing the underlying currents that connect them. But her goal wasn’t to make these works too legible. “As a Muslim, you’re constantly asked to explain your culture, irrespective of where you are positioned in terms of your adherence to the faith”, she says. “It’s almost like the onus of speaking for the whole community is on you. Your surname prescribes both the prejudice outside the community and the expectations within.” As a curator, she felt compelled to resist this pressure—for herself and for the artists. Instead of presenting the exhibition as an exhaustive explanation, she sought to provide just enough context for the audience to engage with the works on their terms. The larger connections—what is happening to Muslims and how the state exerts its power over them—were left for visitors to piece together themselves. For Najrin, it was about honouring the labour of the artists, while placing any additional interpretive effort squarely on the visitors. The idea was also to bypass the state’s gaze. This wasn’t an exhibition framed by victimhood or overt resistance. One would be smart enough to know that the state recognizes only certain narratives, certain kinds of language as threats or affirmation. The exhibition deliberately operated outside of those constraints, refusing to fit into frameworks the state could easily label or co-opt.

For example, what would the establishment make of the nearly indecipherable telegrams sent by a landscape scout searching for Kashmir-like landscapes in Switzerland? Bollywood’s penchant for Kashmir as the idyllic location during the 1960s and 70s dissipated with the rise of armed insurgency in the Valley during the 1990s. Moonis Ahmad Shah’s Telegrams to Cinema from a Mad Landscape Scout blurs fact and fiction, documenting the imagined last reports of a scout whose telegrams reveal his slow descent to dementia as he confronts a beauty bereft of violence—the two being almost inseparable back home. With successive telegrams, the scout’s mark-making disintegrates into the familiar landscape of Kashmir; what looks like Quranic calligraphy is illegible and so does the land it writes. The scout is never found, but what does one more disappearance do?

The precariousness of identity also runs through Nida Mehboob’s Shadow Lives where she turns the lens to the Ahmadi Muslim community in Pakistan, staging photographic works that highlight the apartheid-like systems of exclusion they endure where even the smallest markers of identity—like the way a headscarf is wrapped—can become dangerous. Every image asks the same question: how does existence become a blasphemy?

Mo’min Swaitat’s Palestinian Sound Archive gives a voice to this haunting question. As part of the Majazz Project, a Palestinian-led record label and research platform dedicated to reviving rare tapes and vinyl founded in 2020, the archive captures everything from wedding songs to revolutionary anthems and 80s synth-funk. Tracing his roots to a long line of Bedouin musicians and storytellers, Swaitat connects this rich musical legacy with new audiences by sampling, remixing, and reissuing vintage Palestinian and Arabic cassettes.

Afterall, in a land echoing with bombardment, every tune is a retaliation. Like Swaitat, Nithin Shams also grounds his memories of space through soundscapes as he captures Delhi through a heartfelt composition of field recordings and conversations. ~of many movements and thresholds~ becomes a sonic portal into the city’s layered experiences, shaping his perceptions, practices, and preoccupations.

Similarly interweaving sound and memory, Imaad Majeed documents the azaan across Sri Lanka as a call that transcends generations and geography in Do not roll on the earth, O Golden One. Through spectrograms of azaans and archival materials he creates a resonant space for remembering and protecting Sufi traditions under the threat of erasure.

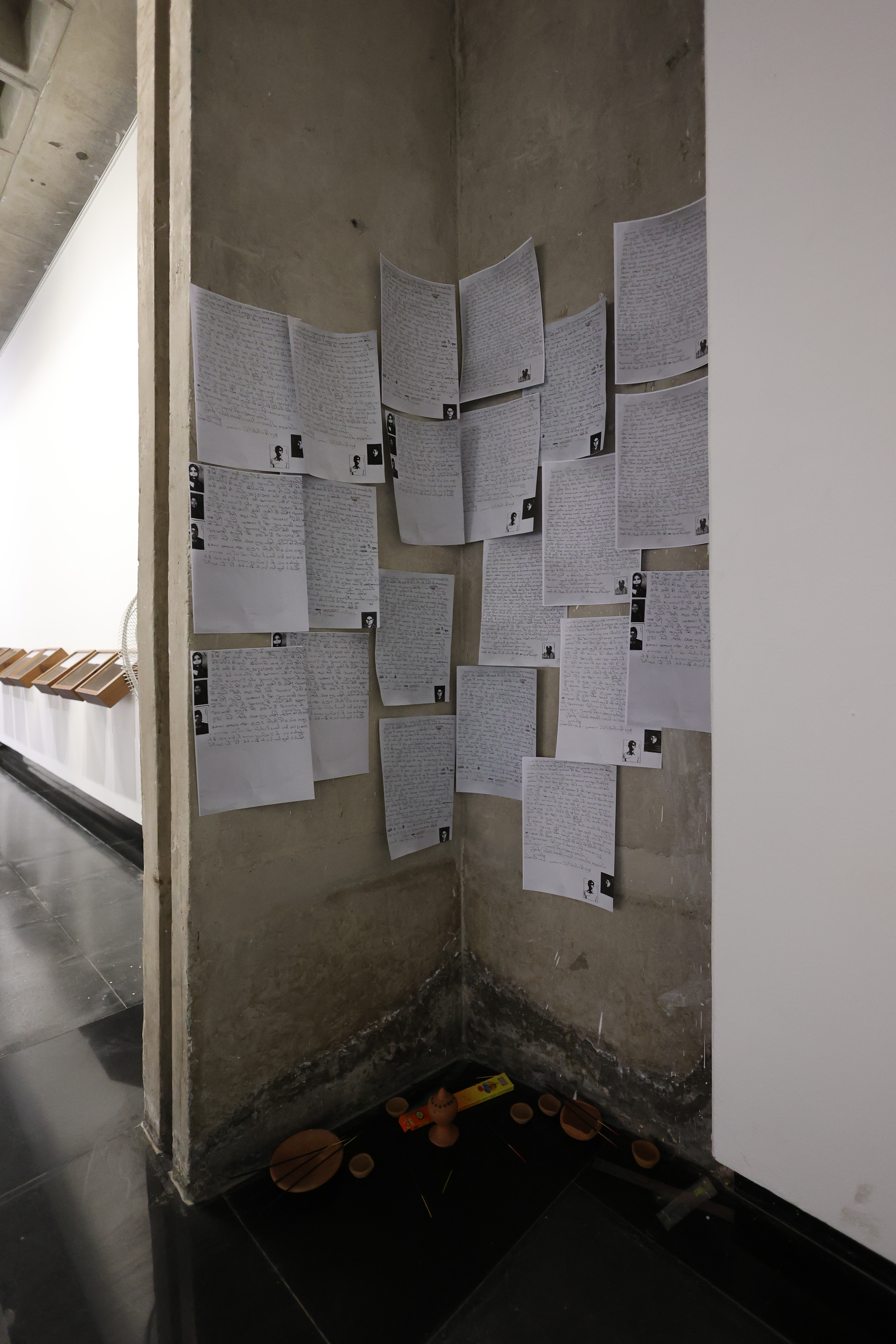

Similarly rooted in place, Taha Ahmad’s A Displaced Hope documents the ritualistic veneration of djinns at Feroz Shah Kotla. Every Thursday, devotees gather to pray, light candles, and leave petitions at the ‘ministry of djinns’, almost mirroring bureaucratic rituals. While clerics collect monetary offerings, the Archaeological Survey of India removes and burns the letters, reflecting the systematic disenfranchisement of the Muslim community in postcolonial Delhi.

Suvani Suri’s Unsettled Fragments takes the reflections on colonial legacies further through an auditory search for Hassaina’s lost song in the archives of the Linguistic Survey of India, a vast colonial-era project aimed at documenting the subcontinent’s languages and dialects.

Khandakar Ohida’s Dream Your Museum further interrogates the politics of archiving through her uncle Selim’s eclectic and deeply personal collection. By transforming domestic objects into artefacts, the work questions hierarchies of preservation and the authority of institutional museums, offering instead a playful and poignant vision of memory. In its own way, each piece in Notes on Omission seeks to address what is amiss—be it in history, archives, or collective memory. Together, these works serve as a counter-archive, pushing back against the effacement of a culture. Every fragmented story, text, image and sound is a cue for the viewer to reckon with erasure.

For Najrin, curating Notes on Omission was as much about accounting for an absence as it was about navigating institutional power. She knew the frustrating formal constraints that came with it—the compromises, the politics. This aspect of mounting an exhibition is a story only she can tell in her own words, though traces of it emerge in the curatorial note, which carries omissions of its own. While the exhibition sought to create a “space of illegibility,” where dissenting voices could converge to “confuse the gaze of the system,” the coerced removal of certain words and phrases from the original curatorial note was not missed by the discerning audience. But how potent is a word anyway compared to an exhibition that is loud and clear about what it stands for? And who accounts for the unwarranted labour of a curator tasked with ensuring that artworks resisting erasure are not themselves withheld from public visibility? As Najrin succinctly puts it, “A curator is also a custodian of other people’s labour. You have to honor that labour, especially when you’re up against institutional power in very concrete ways.”

Working between London and Delhi, Najrin Islam is an art/film writer and curator whose research interest is situated at the intersection of archival politics, institutional omissions, and speculative fiction. She has bylines in several publications, including e-flux Criticism, ArtReview, Runway Journal, Art India magazine, Hakara Journal, Alternative South Asia Photography, Critical Collective, Write | Art | Connect, and PhotoSouthAsia. She has written for catalogues and anthologies by Serendipity Arts Foundation (New Delhi), Museum of Art and Photography (Bangalore), Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022, Rowman and Littlefield (Maryland), and Edition Fink (Switzerland); and curatorial notes for Kunstkasten Winterthur, Project 88, The Guild, Vadehra Art Gallery, and Experimenter. She is a recipient of the Art Scribes Award 2022 and the Art Writer’s Award 2018. She has attended residencies at Villa Sträuli, Switzerland (2019) and La Napoule Art Foundation, France (2023). Najrin is currently working as a Festival Administrator at the UK Asian Film Festival, London.