Synchar Pde

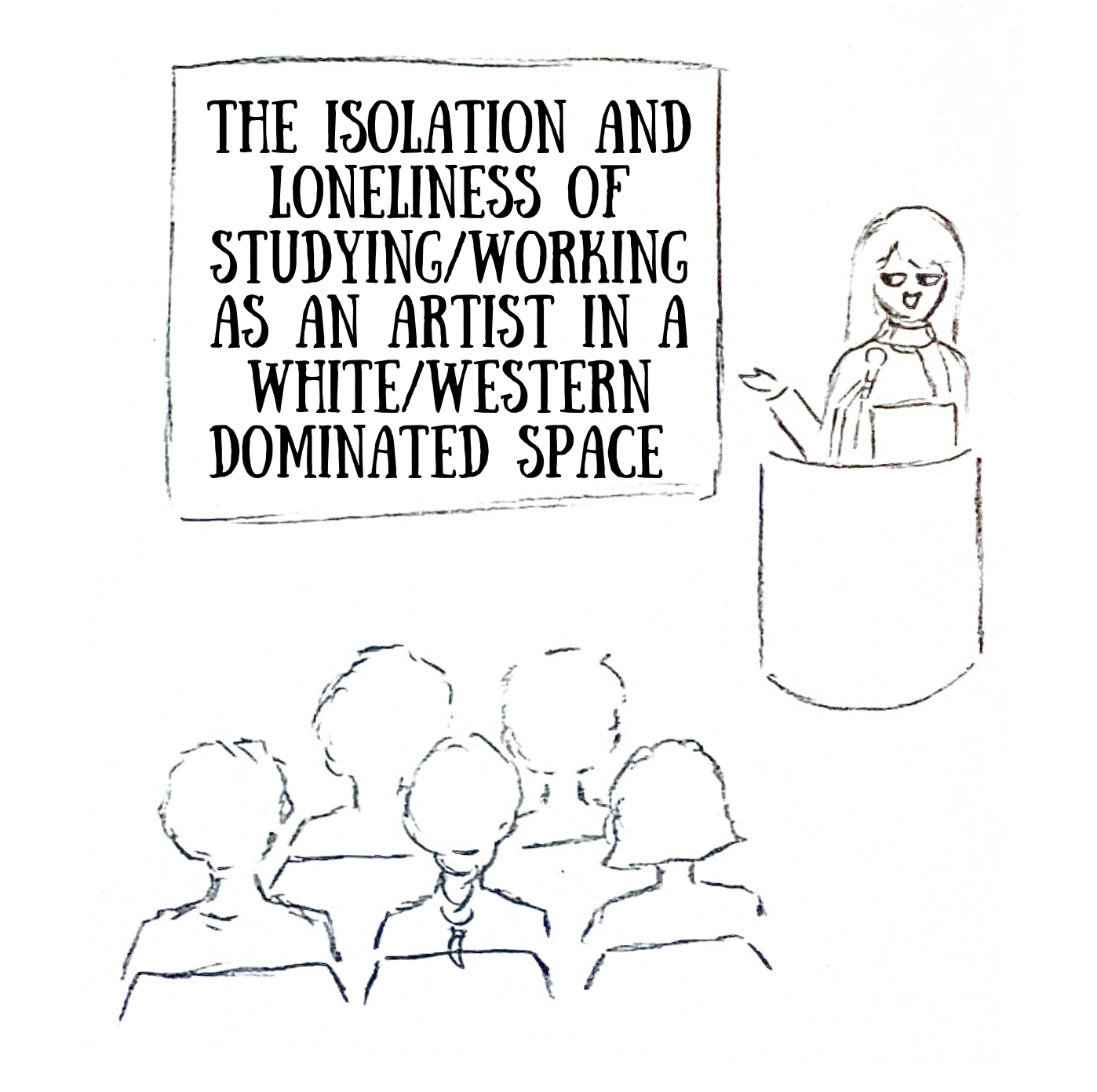

Creating art as an indigenous tribal artist in spaces of privilege is an act of survival and resistance. It is a process often marked by profound loneliness and isolation. In many of the programmes I got in, I was often taken in as part of tokenism. These spaces, while full of opportunities, were also full of silences—after group discussions, after presentations. As the only international student in an art college in the UK, I found myself struggling to stay afloat in a white-dominant space, the gold standard of privilege.

Whiteness is celebrated as the standard we are taught to aspire to—from education to language, beauty, media, music, and so much more. I entered this space feeling inferior and left with a weight of anger and anxiety. I wrestled with making art that stayed authentic to my roots while facing the constant pressure to cater to white expectations. The solitude of this work is heavy: the weight of representing a culture in spaces that don’t share its history or values.

This zine explores some of that isolation, the struggle, and the resilience that emerges from it. It is both a reckoning with the systems that alienate and a celebration of the unbroken ties to heritage that ground and sustain us.

I always had to pre-write my thoughts, rehearse my words, and carefully choose language that would make my work palatable to a Western audience. There’s a certain vocabulary, a specific way of speaking, that we are expected to adopt to make our art ‘relatable’ within their framework. But how do I describe my culture within their sphere of understanding, when their knowledge and perspective are so far removed from my lived experience? How do I reduce something so deeply rooted and vast into terms that fit their narrow expectations? These compromises feel like a constant erasure—a translation that strips away the essence of who I am and what my art stands for.

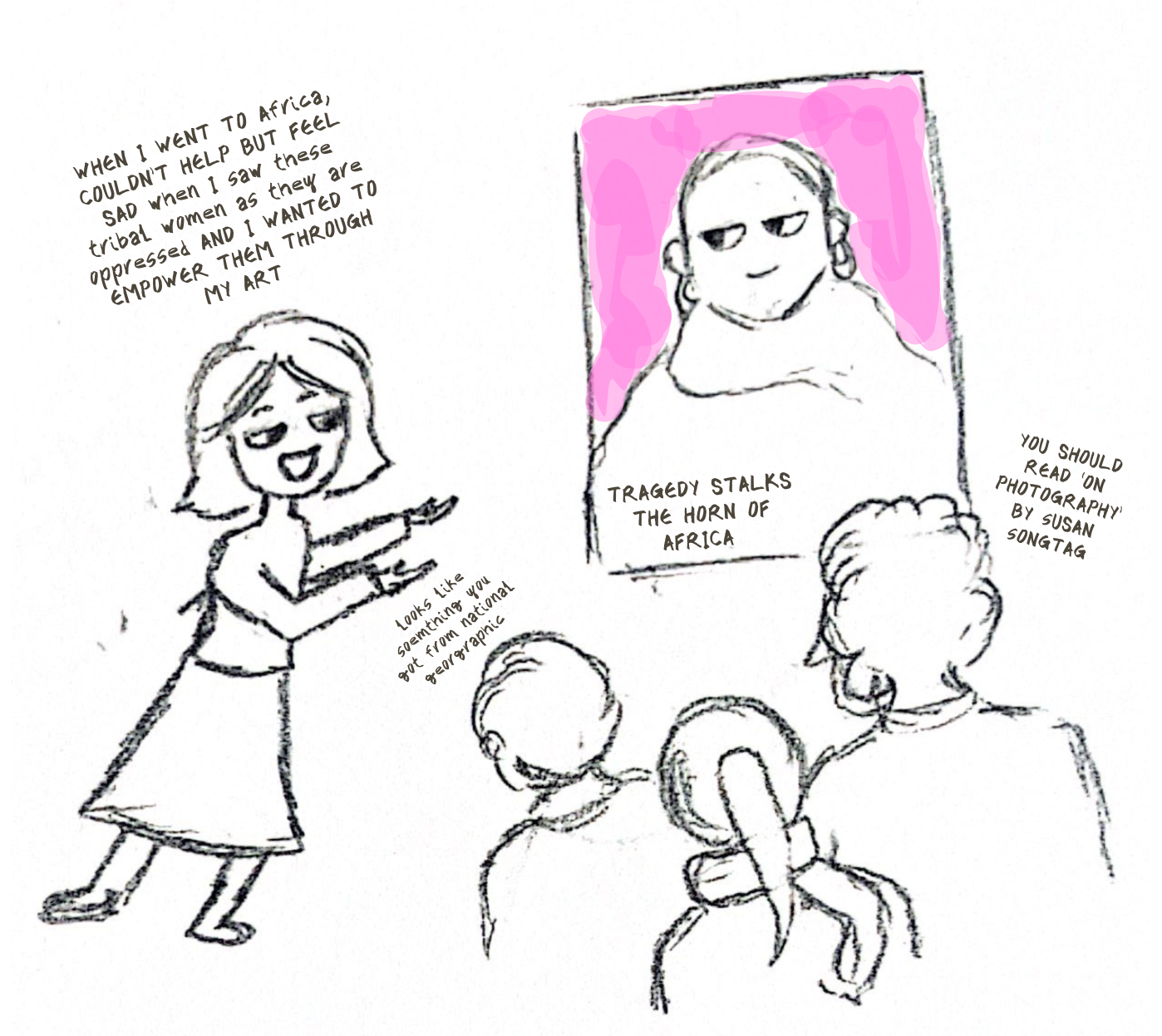

White saviorism is something you encounter in nearly every art space. I remember a girl in my class talking about tribal women in Africa being oppressed, yet she never named the country or the tribe she supposedly encountered. The ‘oppression’ she spoke of seemed to come directly from a white-saviour documentary she had watched; as if we lack agency in our own stories. It’s the same tired narrative that labels our art as ‘primitive,’ reducing it to something exotic or archaic, just like they do with our people.

I wrote and created a shadow puppetry performance based on the stories of the Jaintia queens from my community. The play explored the significance of oral history and how to view it through indigenous perspectives. After the performance, my POC (people of colour) friends immediately understood and engaged with the work, offering insightful criticism. But the rest of the audience? They wanted me to show a map of India and point out where I’m from—*before* I even performed. This happens quite often whenever I share my work. It’s as if my art cannot stand on its own until they first place me on a map, as if my identity needs to be contextualized before my voice can be heard. This is why so many of us are constantly asked to explain and justify our culture before we are allowed to exist within these spaces.

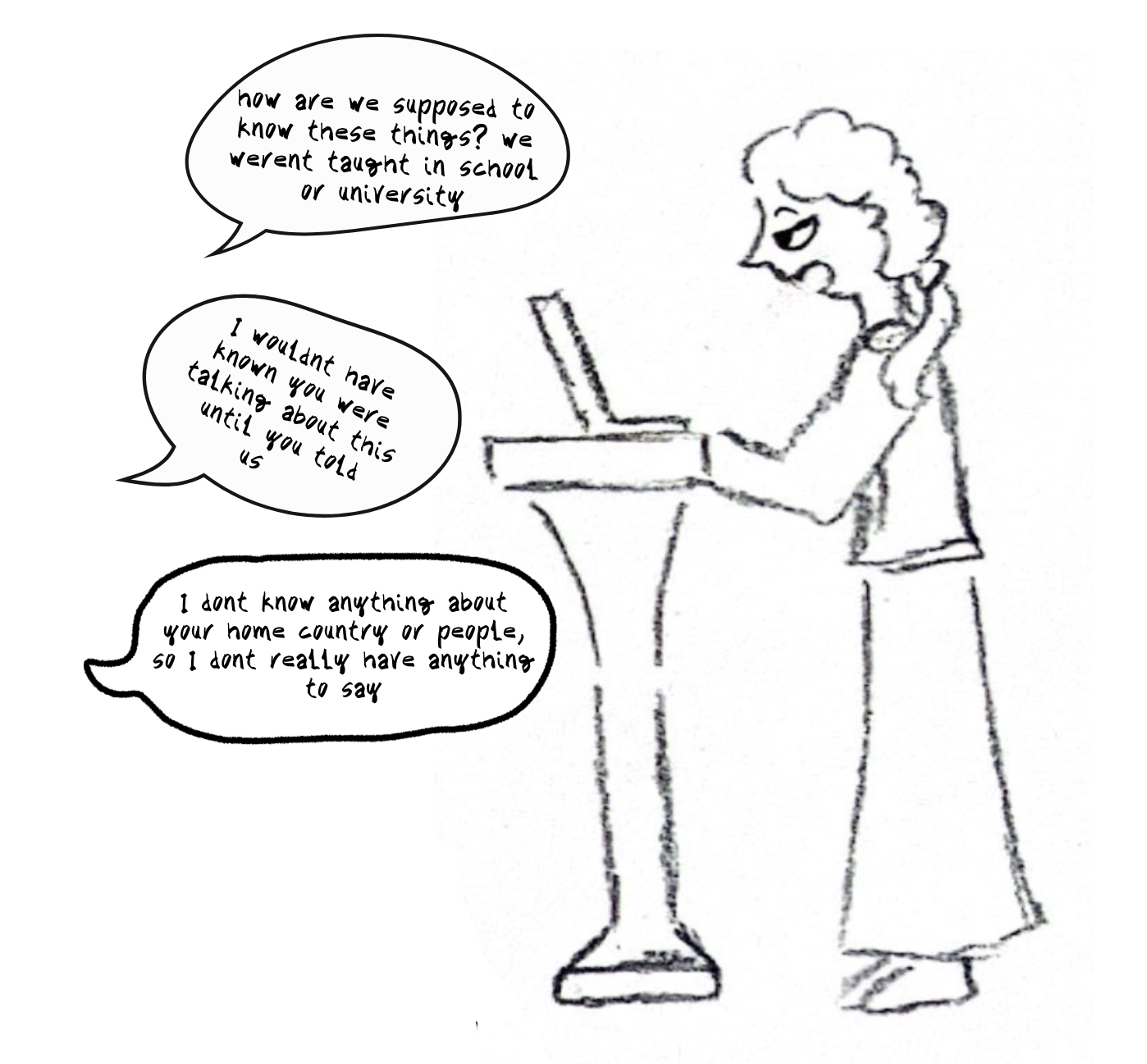

We had an artist-talk in the programme I was part of, with a lovely artist who was very open to listening and engaging. During the talk, one of the members from the programme shared her work, but they admitted they wouldn’t have understood it until she explained the history of her home country. Is it her responsibility to educate them about history? Often many institutions expect work about non-dominant cultures to be “educational” rather than just existing as art. There’s an unspoken demand to justify, translate, or make the work accessible to audiences who aren’t familiar with the cultural context. Meanwhile, artists from dominant cultures rarely have to explain themselves—they’re allowed to just create. It’s an imbalance in whose perspectives are seen as “universal” and whose are seen as “niche” or “other.”

Honestly, how do I create work in a world where most people view culture as little more than an artifact, something to be displayed in museums or galleries? It feels as though culture is only understood on a surface level, its value reduced to aesthetics rather than the depth and meaning it holds. The rich traditions, the craft, and the art forms are stripped of their stories and context, treated as ornamental rather than alive. How do I make art that challenges this mindset, when the very systems I create within seem to deny the significance of the culture I am trying to honour?

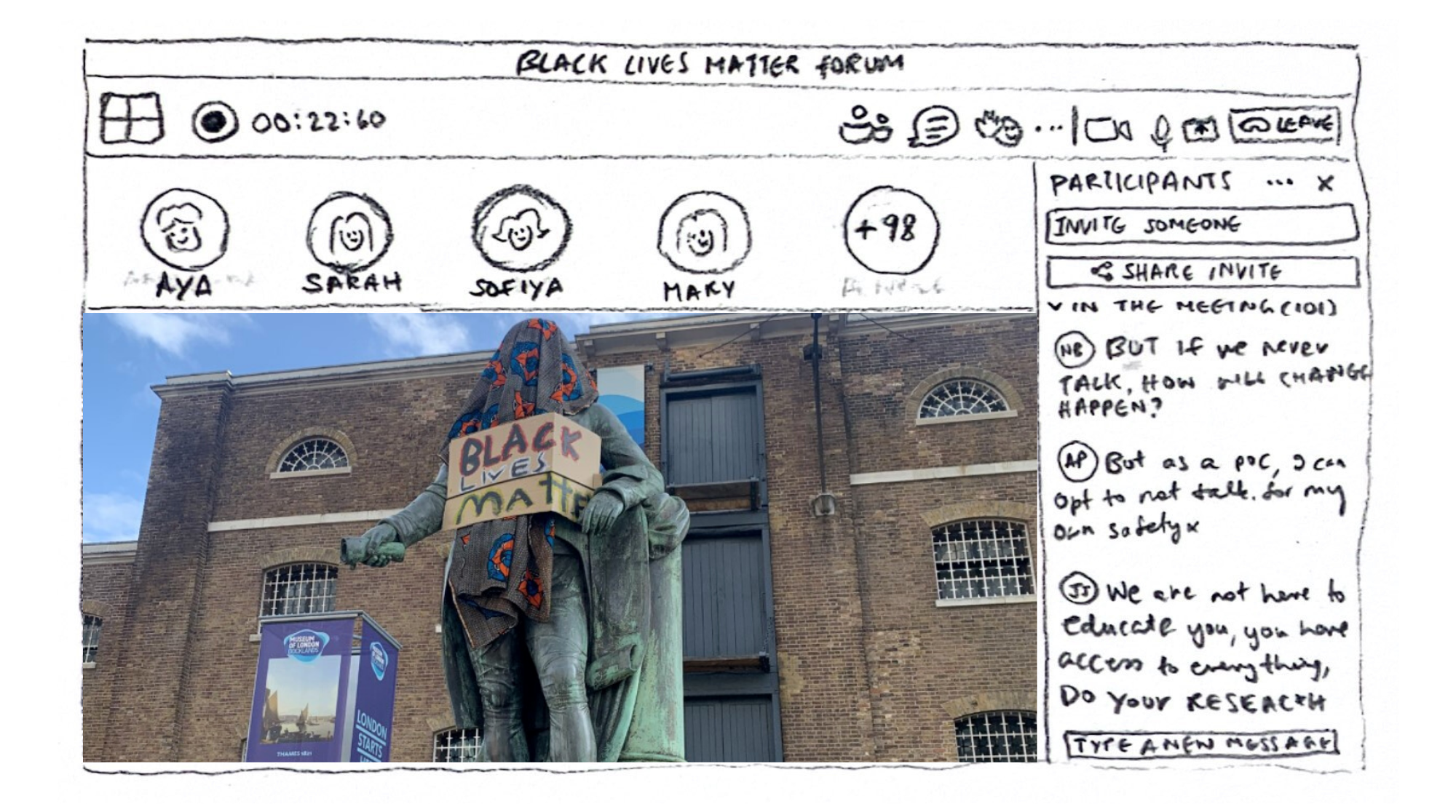

My favorite tutor, Mary Evans, an incredible artist, started a Black Lives Matter Forum in 2020. It began with over 100 participants, sparking important conversations about race and justice. But by the end of the year, our group had dwindled down to just ten. When they found out we were having an exhibition, suddenly the interest revived—but only because they wanted to be part of it. It felt like their involvement was less about solidarity and more about gaining access to an opportunity, revealing how easily people can be drawn to a cause when it’s tied to something tangible for them, rather than out of genuine support or understanding.

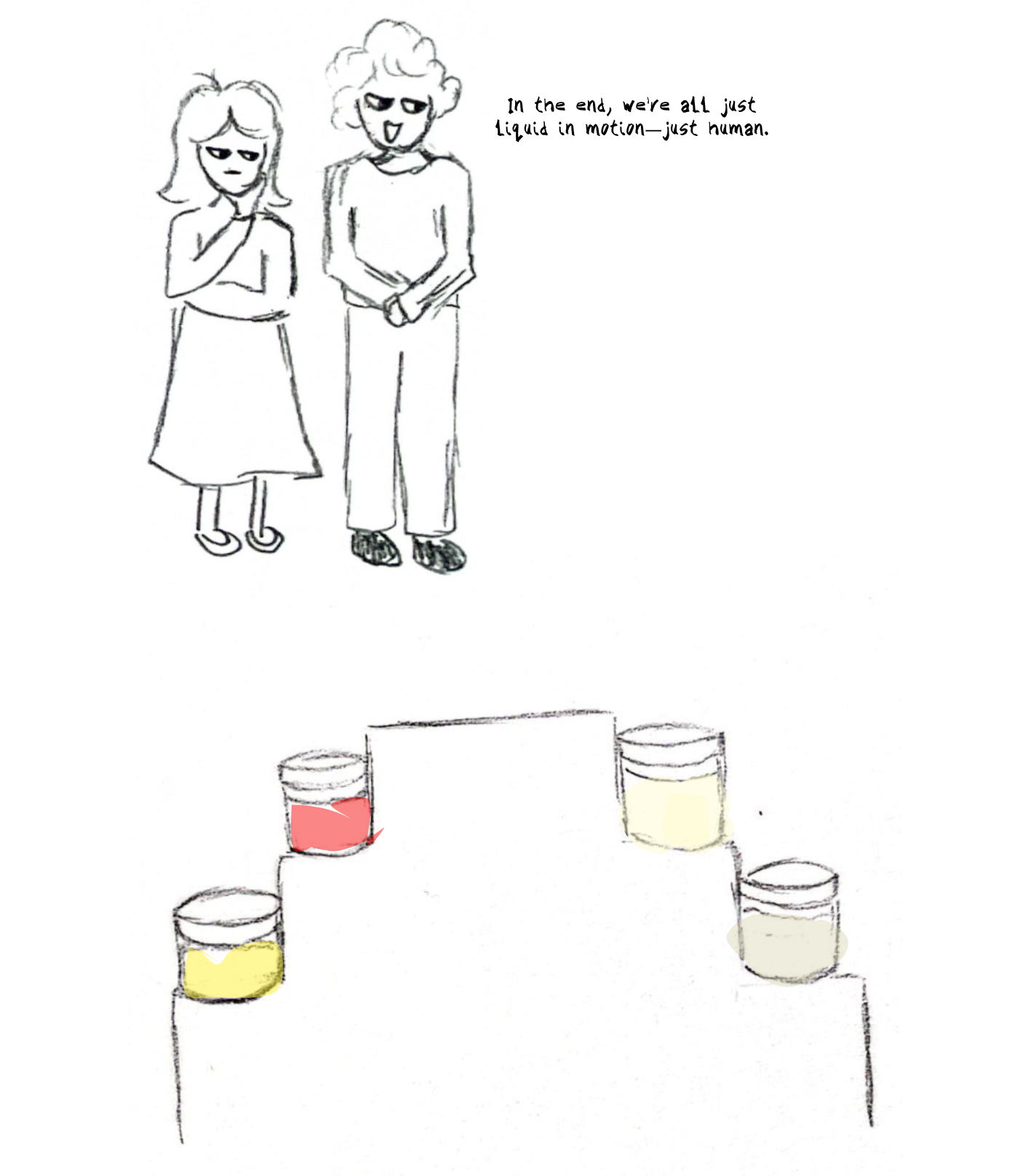

I was often told that the best art is one that shocks people, that leaves a lasting impression. And yet, the art that you hear about and see in galleries is the guy who stored his pee, spit, cum and blood in a container.

During COVID, we had weekly sessions where the main Fine Arts tutor invited artists to give talks. I remember sending email after email, asking for more artists from the global majority to be included. The only POC artists we did have were those based in Eurocentric countries. As tutors, your qualifications should require a broad knowledge of artists and art practices, but it became clear that this wasn’t the case. I ended up learning more about diverse art movements and artists on my own, through places like the Stuart Hall Library, than I ever did in the course itself.

They grouped all the POC together and asked us to make work about our ‘culture.’ This approach pushed many POC to distance themselves, as they didn’t want to be reduced to just their culture. The problem is, very few people are equipped to critique or discuss it with any depth or understanding. So, when we water down our work to cater to these expectations—create art that solely focuses on ‘recognising’ a specific culture—it becomes easier for the audience to engage with it. But in doing so, we lose the complexity and depth of our identities, and the conversation becomes one-dimensional.

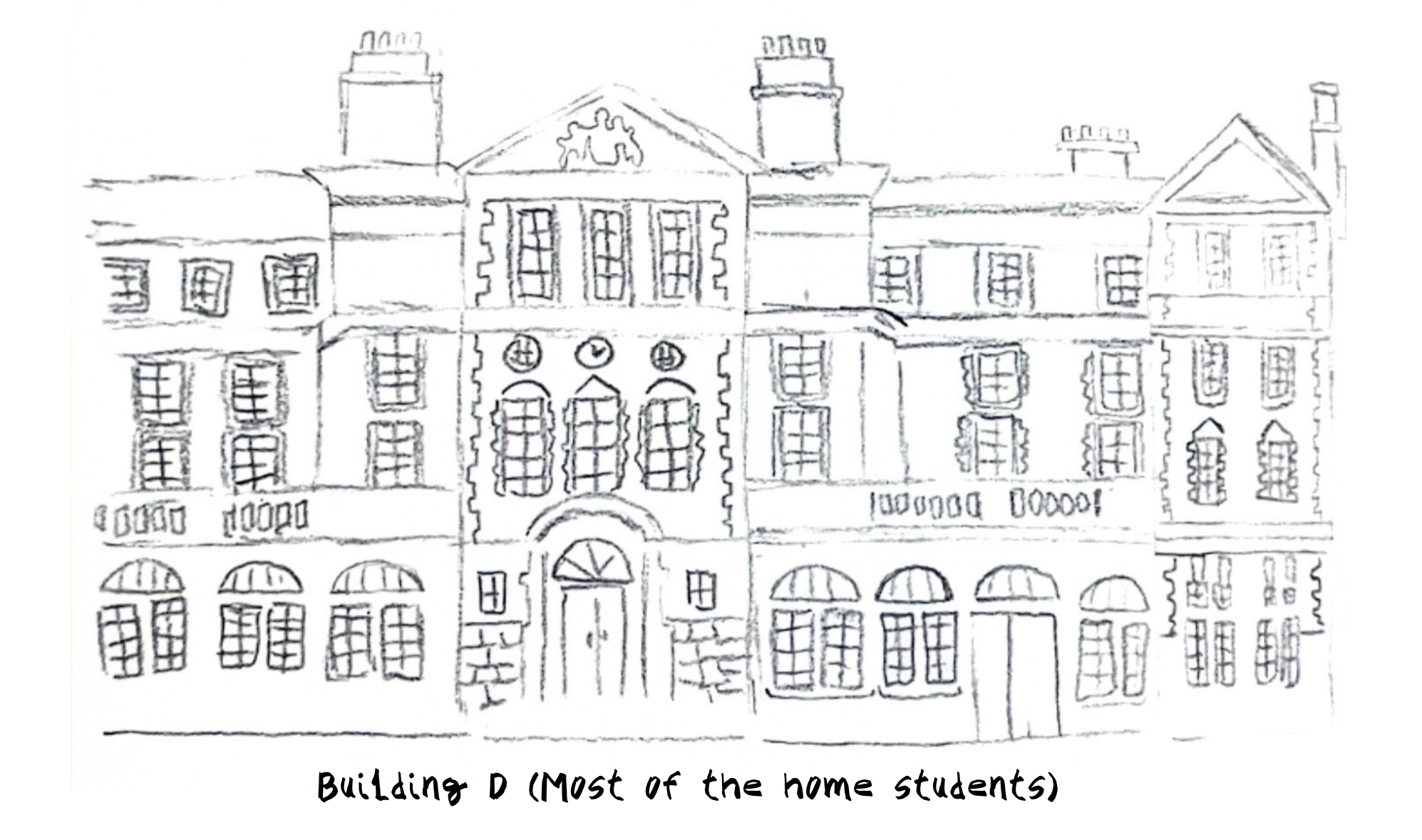

In my final year of university, after a year and a half of being online, we were assigned to two different buildings for our art studios, with one dedicated to the third-year students. However, it quickly became apparent that the majority of home students were placed in one building, while the majority of international students were placed in the other. This division felt symbolic, highlighting the separation and distance between the two groups, rather than fostering a truly integrated, collaborative environment for all.

I didn’t truly understand the value of community until I met people from similar backgrounds in Kalimpong, West Bengal, just a few years ago. It was only then that I realized how much the silence I had endured before had discouraged me, stifling my voice in ways I hadn’t fully acknowledged. In Kalimpong, I experienced something transformative—a sense of belonging. I grew in ways I never had before because I was surrounded by people who already understood who I am. I didn’t have to spend half my time during presentations or discussions explaining why and how I am Indian as well as over explaining my work. Instead, I could focus on my work, my art, and my ideas. That experience showed me the power of community and, now, it’s all I want—to be in spaces where I am seen, understood, and supported.

The dream of studying and working abroad is one many of us share. We were taught to speak English, to know English, to soften our accents—because in my experience, they will praise you for not having one and just as easily remind you how ‘patient’ they must be with those who do. We praise whiteness too much, sometimes blending so seamlessly into white spaces that we forget we were never the ones who chose to be marginalized in the first place.

I am grateful for the experiences that taught me who I did *not* want to be. When I left London, I carried with me a heavy burden of anxiety and anger. Now, all I want is to create something that matters here—to work with artforms that have always existed, to stand firmly on this land. I reject the white man’s approval. My only intention is to remain true to myself, to the hills and the rivers, and to the people I call home.

Synchar Pde is a socially engaged artist, oral history researcher, aspiring kite flyer, sometimes graphic designer and storyteller from Jowai, India. She studied Fine Arts at Chelsea College of Arts (2022). Her work blends storytelling, cultural preservation, and social engagement through alternative artistic practices.