Pritha Mahanti

The pulsating silence of a building under construction is punctured by the slow thud of water droplets from a leaking pipe. Among the rubble are women clad in red and white saris. Their neatly made buns are decorated with tuberose and leaves. Because of its distinct fragrance, tuberose is often associated with sensuality and peace, and thereby commonly used in bridal decorations. Here too, the women wearing this flower are singing a marital hymn. Their passive faces as they sing about a pair of doves and their glittering wedding pavilion, almost matches the eerie hollowness of the construction site. This is a dreamscape of Celestina, a contractual labourer and single, unmarried mother stealing a moment of rest while putting her child to sleep. As the scene unfolds, the unfamiliar no longer seems like an exception. In a way, it sums up Celestina and Lawrence, a movie which, in its muted brilliance, renders the precarity of the human condition in a way that is almost a novelty when it comes to regional cinema from Jharkhand. In this unostentatious tale of heartbreak and hope, an imperiled landscape is as much a protagonist as the characters themselves.

We meet Celestina when she is going through a personal loss—that of a companion with whom she had dreamt of a shared future. She finds herself as a reluctant mother to a child born out of wedlock after the man refuses to marry her. Seething with anger and an inexplicable sense of hurt she remains steadfast in her attempt to pursue a legal battle until soon enough she is arm-twisted by the system to give up her quest for justice. Adrift in her loneliness, Celestina crosses paths with Lawrence, a part-time watchman and contractor in the same city of Ranchi. He has his share of losses too. Having been unable to establish himself as a builder, with the added onslaught of demonetization, he is forced to take up the job of a full-time watchman. It is a reality that the woman whom he planned to marry and whose education and other expenses he had been taking care of, refuses to be a part of anymore. While Celestina resigns into single motherhood and the life of a daily-wage worker, her encounter with Lawrence provides a respite from the unrelenting sorrow they were both caught up in and a new world of understanding opens up between them. Yet, in many ways, Celestina’s sense of this world is a different one, perhaps because in the female experience, hope and despair are too intensely at loggerheads, much like the land she belongs to. As a poor Christian tribal woman, an often-underrepresented and marginalised minority in Jharkhand’s politico-socio-cultural milieu, Celestina’s will to survive amidst the odds could be seen as an ode to her land. As I watched director Vikram Kumar’s first cinematic venture at the Kolkata People’s Film Festival this year, it felt as if a dear landscape was unfolding through the mindscape of the eponymous female protagonist.

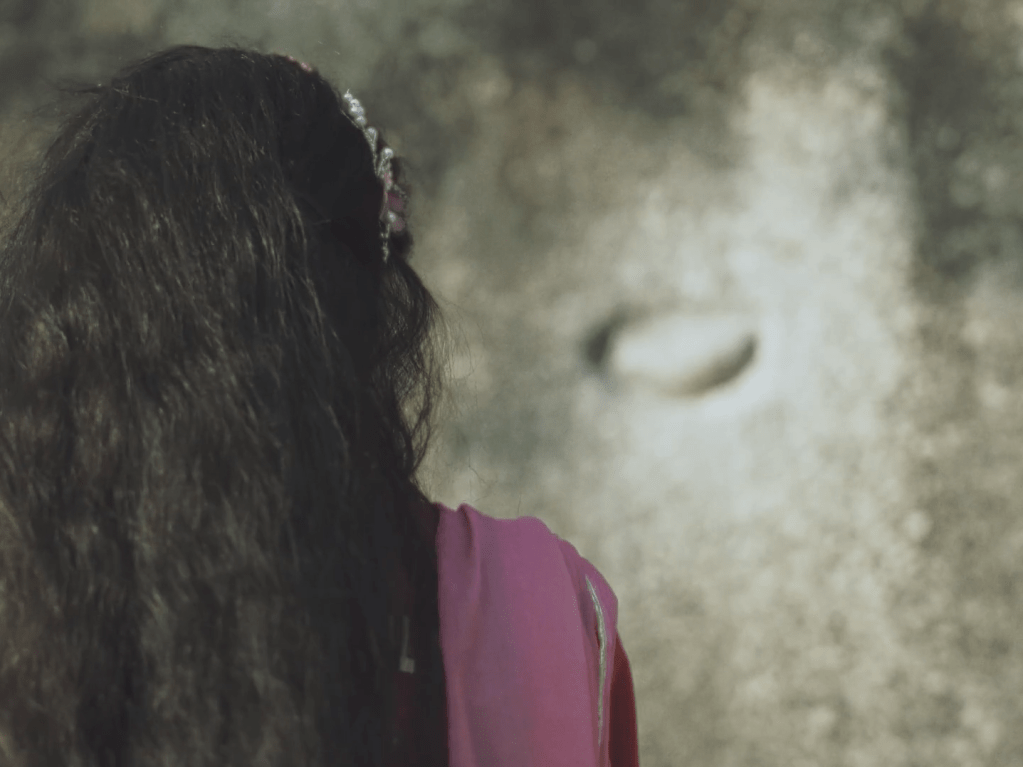

In moments when the film delves into Celestina’s mind, the visual imagery takes on a fantastical character. The land and the lady seem fused into each other, both grieving and healing simultaneously. Early on in the film, when Celestina is overcome by a desire to strangle her sleeping child, we witness another dreamscape where she recalls her visit to the Chand Pahar (Moon Hill). According to local belief, if a pregnant woman wants to know the gender of the baby, she could aim at the moon-shaped spot on the hill. If it’s a hit, it would be a boy, if not, a girl. Although Celestina takes multiple aims hitting at the spot, we know she ends up with a girl child—a fact that seems to be foretold in the close-up of her bright butterfly hair-clip.

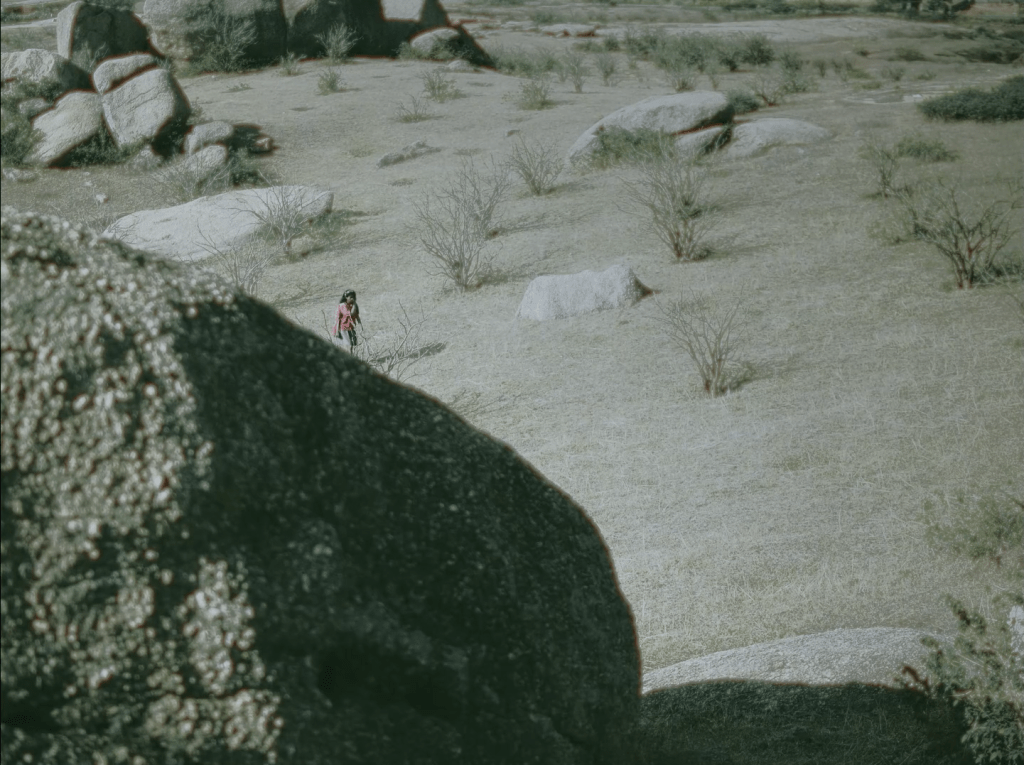

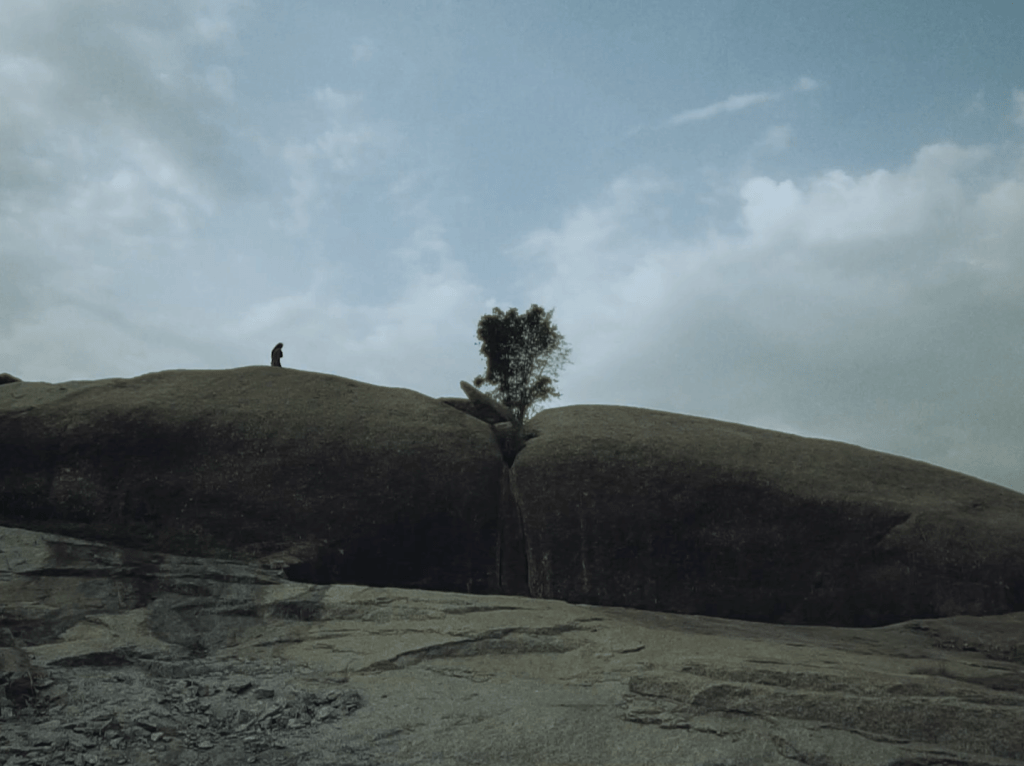

In her dream, Celestina has a conversation with her mother, where the latter tells her it’s not easy for a woman to abandon her child. The reference she uses is that of a seed bursting and germinating inside the body, spreading roots so deep that its presence shall always haunt. As we see Celestina wandering amidst the trees and hillocks, quintessential to Jharkhand’s topography, it almost seems like watching an open womb. A life giving force, the womb is also a mythic space, like the Moon Hill, where reality and fantasy coexist. The landscape too seems to bear this dichotomy.

For the longest time, this land of hills, forests and rivers remained stubbornly autonomous of any external rule until the advent of the British. Despite frequent resistance by tribal groups, the influx of outsiders over time turned this resource rich region into a prey of the powers that be. As indigenous communities continued to be made strangers in their own land, displacement and isolation became synonymous with their existence. Although in 2000 Jharkhand appeared on India’s map as a state in its own right, it could not completely shed-off its woes. After a prolonged battle against its continued neglect and marginalisation, the acquisition of statehood gave rise to new challenges, mostly to do with economic development and resource allocation. Known for the beauty of its rugged terrain and the richness of its land and tribal cultures, today Jharkhand could almost be described as a pale shadow of what it once was as hills continue to disappear, rivers choke up and forests thin out. Yet, it’s far from being written off. This is still a land where its people live through nature and in their resistance embody its force. In the stillness of Nature there lies a promise of rejuvenation, something that I have felt while watching a lush green Parasnath drenched in rainfall, a throbbing twilight amidst the trees at Chaibasa or wandering around the saal forests of Hazaribagh.

The film too seems to imbibe this stillness. What initially seems like lengthy close-up shots of the protagonists’ faces at different moments, is in fact what stays with us long after the film is over. It is quite evident that the director wants us to be with the characters, especially in moments where they feel a jarring sense of loss. There is no hurry to rush to the plot. When I asked Vikram about his thoughts at the editing table, he spoke about the need for creating a familiarity with the characters by allowing the camera to stay on them even in the most mundane of situations.

The impact of this is further heightened by the playfully poignant and captivating compositions of Adrian Copeland and Andy Cartwright. The choice of ambient music was as much a result of financial constraints as it was of a happy encounter. Being an avid music listener, Vikram’s long hours on Bandcamp brought him across the music of Copeland and Cartwright. What is fascinating is the seamlessness with which the scores capture the mood of the scenes, to the extent that even the smallest of notes seem to be composed for the slightest shift in expressions. In opting for Western music, Vikram overturns the stereotype that generally accompanies the soundscape of cinema from this region wherein one half-expects to hear the sound of dhamsa or sarangi or the borrowed aesthetics from Bollywood and Bhojpuri cinema. Celestina and Lawrence adds a fresh breath of air to the corpus of Nagpuri cinema, hitherto marked by imitation and excess, as much with its visuals as with its music. The notes of the cello pull at the heartstrings, so that as faces unravel like landscapes, we move from looking and observing them, to feeling with them.

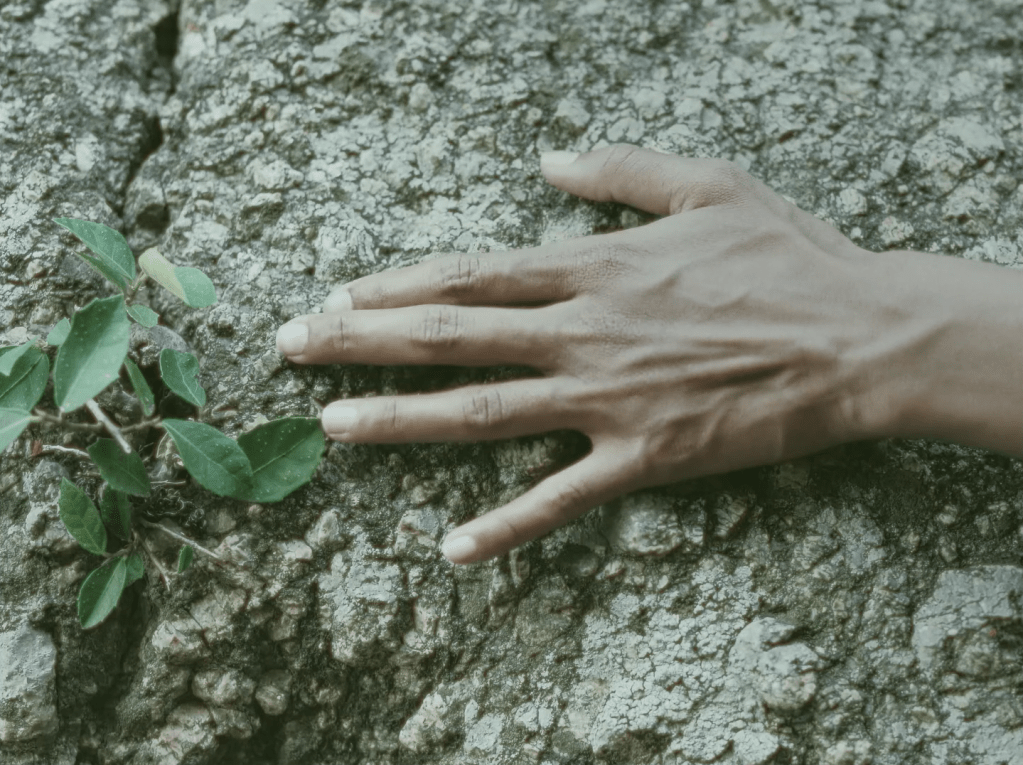

In a way, it is also a filmmaker’s act of resistance in holding our gaze in a highly visual and verbose world of diminishing attention span. So, when I watch Celestina’s despairing face amidst a wedding procession where she is a light bearer, I am reminded of mud houses freshly painted with Sohrai designs, dotting the landscape against a half-blasted hill. The sense of alienation from something that surrounds us, but of which one can never be a part of, is as much a story of Jharkhand as it is of its people. When a bureaucratic state and its corporate offshoots put their mighty weight down on the individualities of a nation, a prolonged conflict between belonging and falling-out ensues. And in this conflict it becomes imperative to preserve what is beautiful, because without it no resistance can be nurtured. In two scenes, that almost seem to mimic each other, we see Celestina’s hand reaching out for the greens, almost like branches that reach out for the sun. It is yet another example of how we end up imbibing Nature’s power of resistance and hope, even as we are caught up between a rock and a hard place.

Despite her circumstances, Celestina’s worldview is wide and wondrous. As she is enthralled by the colourful fish in Lawrence’s fishbowl, she askes him if they could be set free in the waters of the dam. An unsure Lawrence tells her that they might be eaten up by bigger fish. However, for Celestina what matters is more space to swim and grow, albeit the threats. Throughout the movie, there are moments that tell us that she isn’t one to settle for less, while at the same time being painfully aware of her tethers. Perhaps that’s why when Lawrence releases the fish in the dam, we see Celestina, lost in her thoughts, watching the same in the sink—call it her daydream, or a failed fantasy of freedom. In the end, we know that for Celestina the part of her that’s beautiful helps her tide over the crisis as she holds on to her agency and self-worth in a deeply hierarchical society. In the same way we could also think of the stubborn beauty of the slogan Jal Jangal Jameen (Water, Forest, Land) which for centuries enabled tribal communities to indomitably fight for their rights. For a threatened land and people, beauty is ultimately what liberates so that living becomes synonymous with loving.