A special conversation with professor Avijit Pathak

Pritha Mahanti

Japanese artist Fujishima Takeji laid great emphasis on simplicité, the French term for simplicity. His compositions were devoid of any excess, for he believed that, through a painting, an artist should be able to simplify. If you observe his Sunrise over the Eastern Sea, you might understand what he meant. Take away the silhouette of the boat, an apparently unassuming element in the vast landscape, and you know the work would crumble. Attention to detail is what makes such simplicity so profound. Much like Professor Avijit Pathak’s engagement with education. Former professor of sociology at Jawaharlal Nehru University and active writer and columnist, Pathak’s worldview, much like Takeji’s artistic philosophy, centres on the importance of simplicity. Needless to say that such an outlook is oddly fitted for times characterised by a certain excess and decadence. Yet its relevance, as Pathak demonstrates, continues to outlive the times.

As a child growing up in North Bengal, Pathak fondly recalls a teacher from his school who taught them physics and mathematics. He particularly remembers his classes since they went beyond textbooks to a world of interesting stories and anecdotes. One day, he told his students that although he had taught them Newton’s colour theory and optics, it wasn’t enough to have a holistic idea of colour. For that, one had to closely observe sunrise and sunset. The various colours and their alterations at these hours were worth studying and that’s how one would find aesthetics in physics and physics in aesthetics. Pathak says he was too young to grasp the depth of what his teacher said but as he grew up, and took a turn from physics to social sciences in college, he realised the importance of developing a philosophical understanding.

Having attended Pathak’s classes it is quite evident that he carries his teacher’s words close to his heart. The day he mentioned the wonder of a sunset sky, I kept going back to J. M. W. Turner’s painting depicting a famous warship about to be dismantled against a sky lit up by the riot of a setting sun. The image of a changing age counterpoised by a timeless routine spectacle is testament to the fact that, for our deepest understanding, the simple sights of nature will always be the most insightful.

Just like the colours of the sunset, Pathak’s interest spilled over from science to literature, cinema, politics and philosophy. During his university days he developed an interest in Jiddu Krishnamurti’s works. Some of the questions posed by this Indian philosopher of the theosophical tradition stuck with Pathak. Is education only about learning English grammar, physics and mathematics? Have we ever observed a tree? Have we observed anything deeply and through it experienced something very intensely? Back then it amazed Pathak that there was someone who was interested in and was encouraging the development of all the faculties. That is when it dawned on him that education was not simply about having an abstract intellect or a technical skill, but nurturing an overall aesthetics of being.

Such a belief grew stronger when Pathak joined JNU as an MA student. It was an incredibly interdisciplinary campus. Attending Bipan Chandra’s history classes, Namvar Singh’s lectures on Premchand or Meenakshi Mukherjee’s English literature classes deepened Pathak’s idea of education as an inclusive, empathetic and dialogical practice. Pathak recalls an episode where they had to write a review of Structure of Social Action by American sociologist Talcott Parsons. This was obviously a time when the JNU library was not computerised, so students had to manually find books. They were also notorious for hiding books that had fewer copies! Hence Pathak was unable to find a copy of Parson’s work but the smell of dust on books kept him occupied in the library well after his failed search. He drifted towards the arts section and came across a copy of Chidananda Dasgupta’s The Cinema of Satyajit Ray. He grabbed it the moment he saw the title and spent the next few days completely engrossed in it. It is a story he frequently shares with his students, to talk about the joy of accidental discoveries. For him, studentship has always been a fleet of wonder, not something technical and fixed. That’s because knowledge is not a capsule. True learning is to imbibe the spirit of a wanderer.

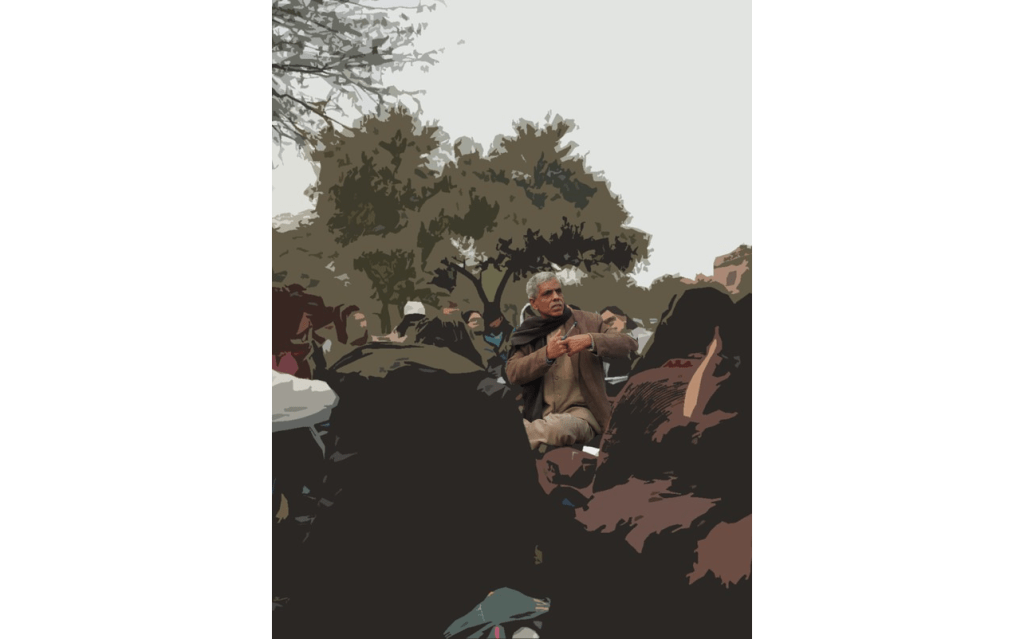

A teacher is also an artist in some sense, he says. Working on a painting is not very different from working on the method of teaching. The way an artist experiments with style and medium, so does a teacher. For Pathak, how he taught a text in the 1990s would be very different from how he would engage with the text now. Just as a teacher changes as an individual so do the students as a generation. As society undergoes fundamental shifts, the terms of engagement with a text alters too. Hence teaching cannot be reduced to a technique, it evolves like an artistic practice. For a teacher, the classroom each day is a space that renews itself. And it doesn’t have to be constrained by walls. Like this monochrome watercolour composition (above), Pathak could often be seen conducting classes outdoors. He says the great thing about such open air classes was that, quite unconsciously, the interactions would be affected by a lot of things; the tree they were sitting under, the song of the birds and the clouds floating in the sky above. The open space naturally encourages conversations, he says. Hence the everyday act of teaching and learning becomes musical and rhythmic. And Pathak quite firmly believes that this is not simply restricted to the teaching of literature or humanities. If one is a good teacher, one will be able to teach physics and maths equally joyfully.

For Pathak, such an approach to teaching is aimed at encouraging two important virtues: empathy and curiosity. The class is where a teacher encounters the self and hence empathy and understanding deepens. The beauty of teaching as a vocation is that teachers are not just there to impart information, but to build curiosity towards knowledge. Pathak demonstrates this with another interesting anecdote. As someone who loves mathematics, he often conducts workshops for children in the fifth or sixth standard. One of the problem solving exercises that he asks them to work on is to calculate the percentage of price difference between Pepsi and lemonade. While working on this there are often some kids who ask why Pepsi is more expensive than lemonade, when in fact the latter is more useful and tasty. They are curious to know why a good product is cheaper. This way, mathematics does not get limited to calculations but a wider reflection on other questions. It becomes a medium for insight into everyday reality. The questions become political.

Yet the hope and enthusiasm with which Pathak talks about education is also clouded by the increasing challenges of the times. Few, he says, would pause for a sunrise or a sunset unless they want to capture it on their smartphones. This age of visual excess is also simultaneously an age of instantaneity where meditative reflection and concentration is gradually eroding. With an abundance of information and our tendency towards quick responses, we rarely feel we have time to pause and think. As a new generation comes of age with tremendous physical energy and intellectual perception, Pathak is reminded of Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman, who in his book, Modernity and the Holocaust, asks how the best minds of a generation could be involved in a genocidal project. What happened to their education? Bauman concludes that modernity has so disproportionately valued an abstract intellect in the absence of other faculties that acts of terror were just reduced to technical skill without any room for moral implication. Pathak warns that instrumental intelligence without aesthetics, creativity or hermeneutics becomes a dangerous tool. He quotes Max Weber’s assertion that with the arrival of modern age where legal and bureaucratic rationality rules, there is a distinct disenchantment, where we are gradually losing our sense of deeper understanding and perception. To add to this, the privileging of instrumental and technocratic thinking that is intensified by neo-liberal marketisation is creating a very utilitarian engagement between a teacher and a student.

In higher studies, as Pathak laments, research has merely become an assembly line production. Yet, he believes there is a bigger threat to education. And that is totalitarianism which is deeply rooted to instrumental and technical thinking. It is an ideology that threatens to destroy the creative spirit with repetition and regimentation, much like the uneasy portraits of the multitude of uniform smiling faces that Yue Minjun (above) creates. Amidst this, Pathak asserts, it is important to remember lessons from the past.

In the winter of 2020 when North East Delhi was caught up in a pogrom against the Muslim population, Pathak found it difficult to carry on with his classes. He then decided to carry a copy of Nirmal Kumar Bose’s My Days with Gandhi to class. Bose was Gandhi’s secretary and companion during the Hindu Muslim riots of 1946 in Bengal’s Noakhali. He recounts a speech by Gandhi on January 4th where he told the crowd that he wasn’t there to talk about politics, but about the simple things of daily life, which if properly addressed could change India’s fate. For Pathak such sensitivity, imagination, rationality and critical thinking were the anchors that a nation in turbulence needed. Gandhi’s words were a reminder that despite the normalcy on campus, it was important for students to not forget that the other end of the city was up in flames.

Pathak admits that teaching today has become more daunting than ever. That’s because we are living in times where the prevailing discourse is characterised by hyper-nationalism and a majoritarian frenzy. Even our smallest acts are being dictated by the powers that be. And any disobedience has its repercussions. It’s a fear that a large section of the people is paralysed by. Our neighbourhoods today reflect the eerie and sinister normalcy of Gulammohammed Sheikh’s Sleepless City (above). The conscience of the citizens seems to have withdrawn somewhere behind the darkened doors.

Yet Pathak is not one of those people who could easily fall for hopelessness. He still believes that it is possible to teach kids to notice a dew drop on the leaf, or the wonders of a night sky, since without these any teaching would be hollow. The development of the faculty of observation and mindfulness, he says, is crucial if one were to value the pursuit of education. Ultimately one should be able to confront oneself in the quiet of one’s own mind.

It is this satisfaction with the self that has prevented Pathak from engaging himself with some other institution post retirement. Yet he often faces this tiresome question, “How do you spend your time?” When I ask him what his response is, he takes a sip of coffee, smiles and says, “For me every moment is alive. Me chatting here with you, this is eternity.”