A special series on the visual world of Indian cinema

By Pritha Mahanti

A portrait is paradoxically a moment frozen in time and is also continuously shaped by it. What we read in a portrait is not simply what it documents or what meets the eye. We also find in it traces of the contemporary, like a chronicle of what was and what will be. It comes across all too well when we think of a nation’s portrait in cinema. Every film is at once a memorial and a mirror. And over time, through recurring motifs, cinema becomes a visual palimpsest of our collective psyche. Caught up in a time when the nation’s image-building exercise seems to be taking a toll, we look at a series of unflattering reflections that serve as a strong reminder of the pitfalls of complacency. Each entry of this series will look at two movies, set at least a decade apart from each other, but forming a continuous shape-shifting portrait of a nation at odds with itself.

Love and a Tale of Despair

For the third part of our series we have two interfaith couples plagued by their respective faiths in a nation that has progressively prioritised hate. While at one level these are indeed tales of rebellion, one cannot help but wonder at the absurdity of it all. Why is it that in a nation forged over centuries on a myriad mix of religions, one still has to battle it out to make place for love? While the answer to this could be a chequered history of irreconcilable differences, it still doesn’t account for the blatant disregard of the syncretism that was woven into the social fabric of the nation. What is most tragic, however, is how hate has been institutionalised.

For Shekhar Pillai and Shaila Bano from the 1995 film Bombay and Ahmed Shaukeen and Jyoti Dilawar from Love Hostel (2022), freedom is but an unforgiving choice. Being interfaith couples, even before having to deal with a hostile society and system, it is the family they have to battle. In Bombay, Shekhar and Shaila belong to the same village and their romance starts out as a classic cinematic cliche, one where it is love at first sight for the man who would fight the world for his beloved. Shekar, a journalism student in Bombay on one of his visits back home falls for Shaila who, though initially shy and reticent, eventually reciprocates Shekar’s feelings. For their orthodox Hindu and Muslim families this is evidently unacceptable. However, there is no melodrama spent in convincing the kins. Each is squarely defiant to stand up for the union. When Shekar’s father tells him he cannot marry a Muslim while he is alive, Shekar promptly replies that he doesn’t have time to wait for his father’s death. When Shaila’s father asks her to promise never to be in touch with Shekar, she quietly refuses. Thus both of them end up in Bombay, the brimming metropolis where they get married and start a life beyond the shadow of their families. However, the shadows of their gods loom large and it is only a matter of time that the city rears its ugly head.

Fast forward to 28 years later, in Love Hostel, Ahmed and Jyoti’s romance is presented like an unsaid backstory. The cliche is gone. One seems done with falling in love, it is how to survive it that really matters now. Unlike Bombay, Love Hostel depicts a real world dystopia where there is no scope for redemption. Ahmed comes from a humble Muslim family in the meat business whose father is falsely arrested on charges of terrorism. Whereas, Jyoti’s family is under the strict command of her grandmother, Kamla, a heavyweight politician and matriarch who swears by her family’s honour. Upon discovering that Jyoti has fled her arranged wedding to be with Ahmed, Kamla vows to kill Jyoti herself for the ‘shame’ she has brought to the family. And therefore begins the chase wherein a savage hitman called Dagar is let loose to hunt down the couple.

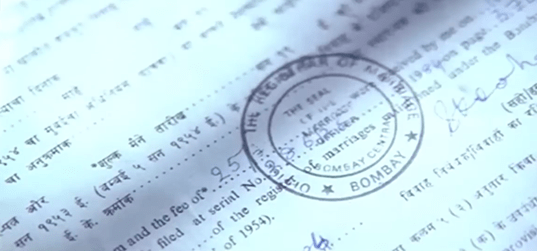

However, the failure of families to acknowledge love does not prevent it from seeking its due rights. In Bombay, Shekar and Shaila register their marriage in presence of Shekar’s colleagues as witnesses, and in Love Hostel Jyoti and Ahmed are able to get the court to approve their marriage with the help of a friend and an advocate. The legal stamp on a forbidden union, even as it comes as a respite, is fraught with the difficult question of its afterlife. That’s because state approval without social acceptance is more often than not an uncertain territory. It also reveals democracy’s failing act wherein a clean stamp on paper translates into an equally murky reality, the degree and nature of which vary with the times. While in Bombay love finds a happy home and is able to preserve itself despite the disruptions, in Love Hostel it is made to pay a heavy price.

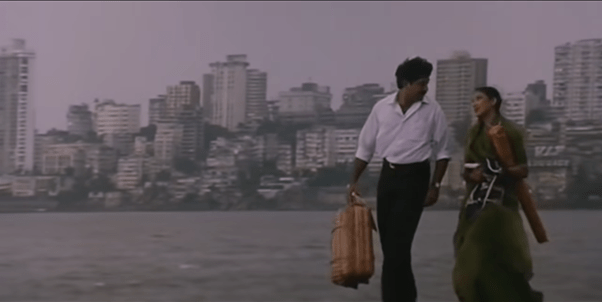

For Shekar and Shaila as they head home after getting their marriage registered, love takes a fresh breath of air in a city that promises to be a refuge. For Jyoti and Ahmed, however, wedlock becomes synonymous with exile. With the looming threat of Jyoti’s family, the court grants the newlyweds protection in a safe home for runaway couples until the next hearing. What should have been a flower bedecked gateway car is instead a police van, for such is the menace of politics and prejudice that intimacy leads to a kind of incarceration. And a safe home, as we know all too well, is not the most ideal honeymoon suite.

While the images of happy domesticity in Bombay are in stark contrast to the absurdity of a nondescript lodging for runaway couples in Love Hostel, the idea of hope resonates in both. Guarding their world from the feverish majoritarianism gripping the country, Shekar and Shaila become parents to twin boys. Their happy home thrives against the growing unhappiness of their gods outside. This hope, however untenable, also sustains Jyoti and Ahmed. The picture of them taking up a corner in a rundown hallway filled with other interfaith couples is a poignant reminder of the lengths to which love can go in order to preserve itself. In this strangely godforsaken space, love blooms in a shared solidarity against the many odds pitted against the occupants from beyond the walls of the safe home.

Yet the wildfires of hatred are hard to tame. As Hindu extremists hit the dome of a 16th century mosque, the reverberations spread across the country. Cosmopolitan Bombay transforms into a communal nightmare. The world that Shekhar and Shaila nurtured is sabotaged by fanatical forces and an incompetent, unreliable and biased state machinery that is in cahoots with the Hindu majoritarian agenda.

The twin boys are nearly burnt alive by rioters for their mixed parentage. It is a rude irony that before their birth Shaila had assured Shekar that their children would have two gods to look after them. Unfortunately, it is a world in which gods are pawns in the political establishment. And as Love Hostel depicts, this establishment is defined by a lawlessness so severe that it unleashes monsters like Dagar which it fails to control. He is a man who believes that he is serving society by ridding it of interfaith unions and that is what makes this trigger-happy maniac such a dangerous figure. When hatred becomes an ideology, it is at its invincible best.

While it might be possible to view Bombay like a blip in the story of nationhood, the same is not possible with Love Hostel, which seems like stepping into a dark mode without any escape route. Every act of violence in the former could be perceived as being magnified in the latter. In Bombay, Shaila’s brickmaker father, Basheer, is slighted by Shekar’s father Narayan who incites him by placing an order for a truck full of bricks with ‘Ram’ engraved on each, meant as a contribution to the building of the infamous grand temple. Immediately, a scuffle breaks out that is quickly restrained by fellows on either side. This othering of the Muslim identity takes a sinister form in Love Hostel where we see police raiding Ahmed’s meat shop and forcibly taking his father away on charges of terrorism. It is a stigma that weighs heavily on Ahmed who is further rendered helpless by being forced into an illegal meat racket. Every step of his marginality makes him smaller in the notorious system within which he seeks protection.

Whereas Bombay holds the promise of reconciliation, be it between the warring parents or a divided citizenry, Love Hostel is a ghastly portrait of an absolute and unforgiving horror. In the former filial and community ties are not only restored for the sake of brotherhood, but also valorised. In the latter, such ties seem like a far fetched luxury. Jyoti’s and Ahmed’s families never meet. Jyoti’s father is shown to be a meek but compassionate man who ultimately stands up to his vicious and vengeful mother, Kamla and his irascible younger son and wife. On the other hand Ahmed’s mother’s dementia is just another extension of the erasure that the Muslim body is subjected to. And while this is not new, in the current times it has taken on a particularly nasty character.

Both movies belong to incredibly difficult times where the basest instinct of humans are laid bare and the first casualty is love. While Bombay’s was an era that could fight hate by renewing its commitment to secular ideals, hate now has reached a point where the word ‘secular’ has become an affront. Neither Jyoti nor Ahmed manage to survive this fiercely oppressive system and therefore it is the snowy wilderness of the imagination where they unite. When, in fact, they could have been the happy family chasing the rain on Bombay’s shoreline.