A special series on the visual world of Indian cinema

By Pritha Mahanti

A portrait is paradoxically a moment frozen in time and is also continuously shaped by it. What we read in a portrait is not simply what it documents or what meets the eye. We also find in it traces of the contemporary, like a chronicle of what was and what will be. It comes across all too well when we think of a nation’s portrait in cinema. Every film is at once a memorial and a mirror. And over time, through recurring motifs, cinema becomes a visual palimpsest of our collective psyche. Caught up in a time when the nation’s image-building exercise seems to be taking a toll, we look at a series of unflattering reflections that serve as a strong reminder of the pitfalls of complacency. Each entry of this series will look at two movies, set at least a decade apart from each other, but forming a continuous shape-shifting portrait of a nation at odds with itself.

Kings and a Tale of Caution

For the second part of our series we have two kings with their grip firmly around their kingdoms. However, despite their attempt to establish a draconian perfection, they unleash a fatal disruption. One is perhaps quick to assume that this cautionary tale is for kings. But kings, as we know, are too buoyed by political authority to ever grasp its pitfalls. Therefore, these timeless tales are for both rulers and sympathisers whose idea of power is an absolute one, without room for doubt or dilemma.

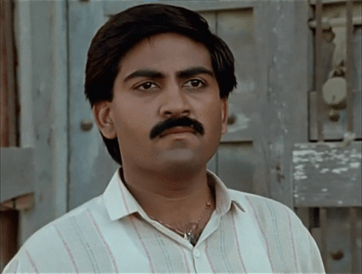

Hirak Raja, from the 1980 classic Hirak Rajar Deshe, and King Bhadrabhoop from the 1992 underground gem Hun Hunshi Hunshilal, are both introduced as self-indulgent, deluded and despotic sovereigns for whom every problem has an easy solution—denial. Turning their totalitarian fantasy into reality with every passing order, both kings are shown to be guided by personal whim than any particular ideology.

Both Hirak Raja and King Bhadrabhoop are preoccupied with an ongoing experiment that seeks to put an end to any kind of dissent. Hirak Raja is thrilled when he finds out that his court scientist has invented a brainwashing chamber. Once inside this mind-altering device, subjects would be fed phrases in praise of the king which they would then parrot being rendered incapable of exercising rationality. Somewhat similarly, Bhadrabhoop eagerly awaits the launch of the Onion Project, a strong repellent to deal with the ‘mosquito’ menace raging over his kingdom, Khojpuri. These ‘mosquitoes’ are a euphemism for the discontented masses throughout history, ceaselessly at odds with the powers that be. They are the ‘anti-nationals’ that Bhadrabhoop wants to eliminate so that Khojpuri remains unquestioningly obedient to him.

In both the movies, the kings’ propensity for deception is well captured in the frames where they are shown taking in the fragrance of flowers. Hirak Raja is offered a bouquet of paper flowers designed by the court scientist and is impressed with how real they smell. Whereas we see Bhadrabhoop intoxicated with a yellow rose as he poops. One can imagine the olfactory onslaught, but Bhadrabhoop seems unfazed. Fascism is like a fragrance, it is seductive to many. And as Israel’s right-wing justice minister once demonstrated in an ad campaign, it could be made to smell like democracy too!

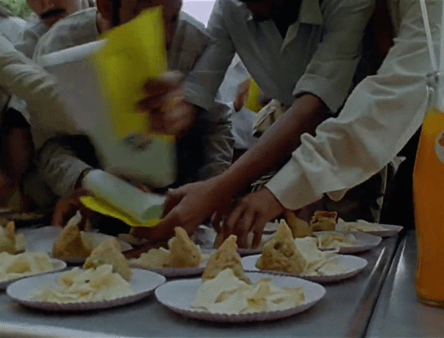

And there is enough at the disposal of the despots to keep a steady supply of such a fragrance. Hirak Raja sits over a rich and growing stock of diamonds and feeds his pet ministers with a necklace each from time to time. As for Bhadrabhoop, his press meet turns out to be a spectacle of callousness where a motley group of journalists descend on the snack counter like depraved flies. In both Hirak land and Khojpuri, it is a strict transaction—mind for material. The ministers, journalists and fanatic citizens we witness in these two films seem to know the tricks of surviving a regime as hostile as the one they are in. Hence such a transaction acts as a durable balance. But there is a huge mass that is outside this arrangement. It includes those invisibilised groups like farmers, miners and workers for whom unending toil and loyalty to the throne are neither recognised nor rewarded. And for any kind of defiance or disobedience, the regime has its design. However, even the most oppressive of systems cannot insulate itself from sparks of rebellion.

We find two such defiant figures in Udayan Pandit and Hunshilal whose ultimate showdown with authority, while having different consequences, seem part of the same parable. Udayan Pandit, the village schoolmaster in Hirak Rajar Deshe, is an obvious exception because unlike the other characters, his dialogues in the film are not rhymed. In keeping with the format of a quintessential political satire, he is therefore shown as a free thinker who pulls out all the stops to rid his land of the evil king. Aided by the wandering musicians Goopy and Bagha and his students, Udayan hatches a plot to give Hirak Raja a taste of his own experiment. In an unforgettable climax Hirak Raja, along with his ministers, after being forced into the brainwashing chamber, join the rest of the villagers to pull down his own statue.

Hunshilal, however, is not a rebel when we meet him first. He is introduced as a diligent and disciplined junior scientist at the Queen’s Lab who comes up with a new vaccine to counter the mosquitoes. Yet, falling in love with his colleague Parveen leads to an overhaul of his beliefs and being. Parveen is revealed to be one of such mosquitoes and the secret owner of the red diary (an archetypal revolutionary symbol) that the establishment badly wants to destroy. For Hunshilal, this rude awakening is fraught with danger. Disillusion leads to despair, and despair leads to dissent. But the regime proves too powerful for Hunshilal’s rebellion and he is ultimately forced to the lobotomy bed. Yet an inconspicuous attack awaits the king.

On the sidelines of a wrestling match arranged for Bhadrabhoop, a young boy aims his pistol and fires at the despot. Compared to Hirak Rajar Deshe, this is certainly a placid climax. But that is because Hun Hunshi Hunshilal ends on a far terrifying note—the swearing in of a new king who looks exactly like Bhadrabhoop. Though he assures Khojpuri of a new dawn, one can sniff the sham. Nevertheless, it would be foolish to read it as hopelessness. In fact, this is where one can recall a scene from Hirak Rajar Deshe where another young boy aims his catapult and disfigures Hirak Raja’s newly unveiled statue. It is a subversion every establishment needs to be subjected to, fascist or otherwise. For, why wait on the sidelines to see untamed power raze everything to the ground? So aim at the soaring signs of dictatorial authority and fire!